The United Nations are currently negotiating a new Agreement for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). This agreement seeks to regulate the access to and sharing of benefits from marine genetic resources (MGRs), to establish area-based management tools (ABMTs), including marine protected areas (MPAs) on the High Seas, to assess the impact of activities on the marine environment through environmental impact assessments (EIAs), and to strengthen marine scientific research and guarantee capacity building and technology transfer (CB&TT). The recently published article “The Voice of Science on Marine Biodiversity Negotiations: A systematic Literature review” by Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki and Alice Vadrot informs international ocean governance by untangling the complex BBNJ negotiations, highlighting the policy relevance of existing work, and facilitating links between science, policy, and practice.

Science and Knowledge on Marine Biodiversity Negotiations

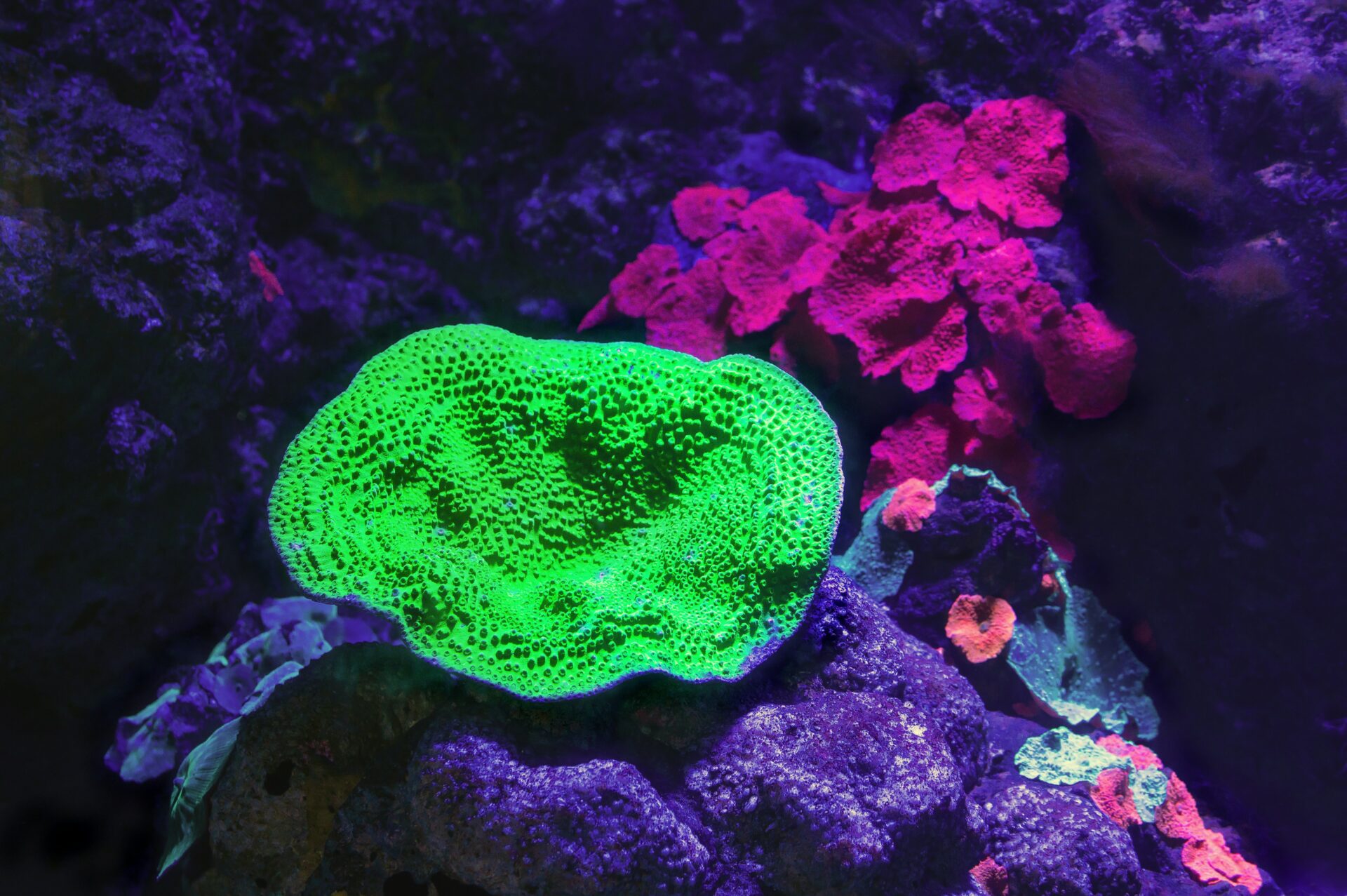

Photo credits: Ines Alvarez on Unsplash

Oftentimes, it is expected that international policy-decisions are based on the “best available science and knowledge”, especially when areas and resources at stake are “global commons” and belong to no one and everyone at the same time. This is the case with the ocean, where state governments are currently negotiating about the future of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. But what is meant by such “best available science and knowledge” remains undefined. Various stakeholders are valuing different forms of knowledge and grant science and knowledge of different powers regarding decision-making about activities on the High Seas. Most people agree that regulating the ocean should be based on sound knowledge, retrieved by scientific methods, and approved through peer-review of other scientists before publication. Increasingly, there are calls to integrate other forms of knowledge, including traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, and local knowledge of practitioners, civil society and the private sector.

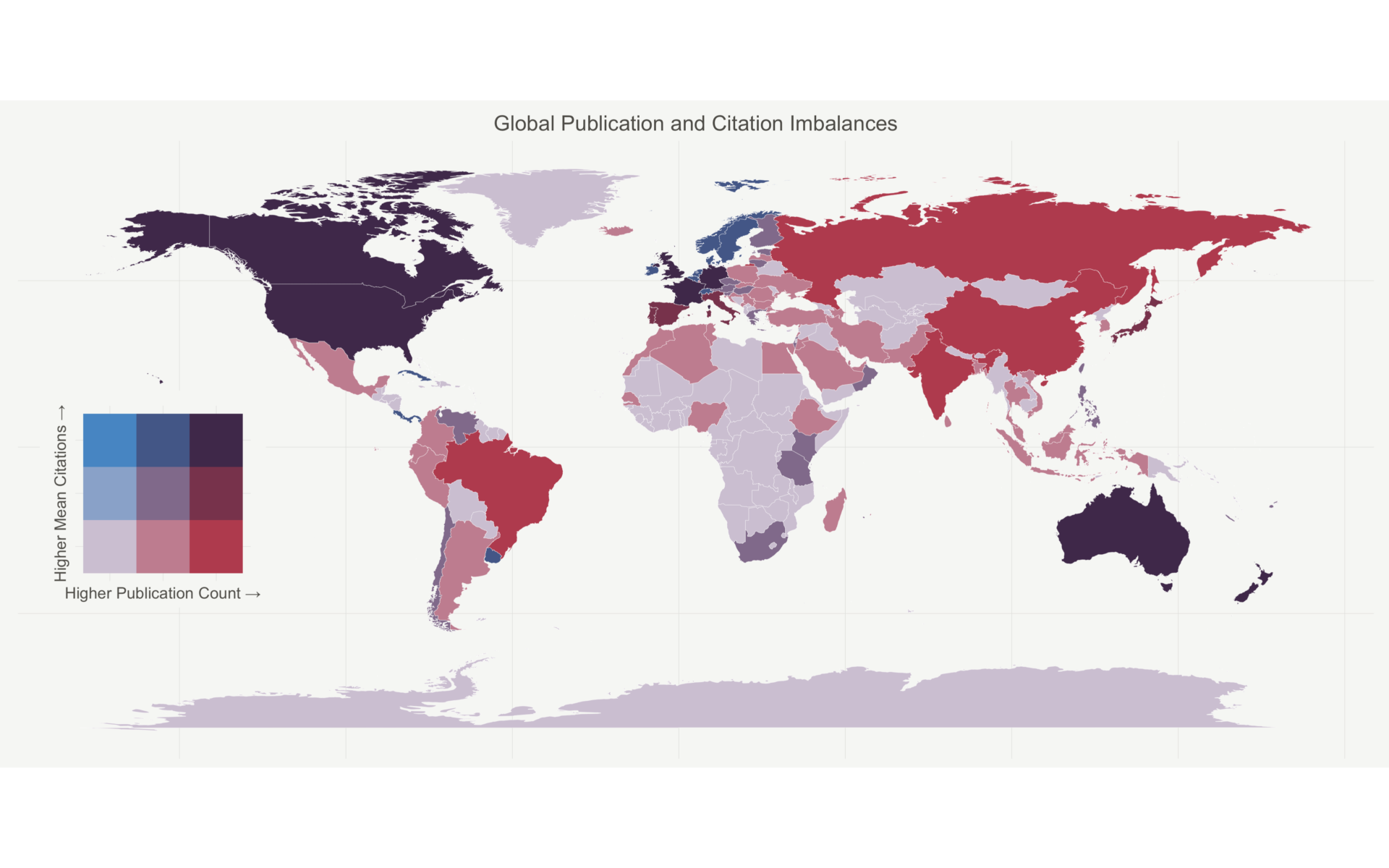

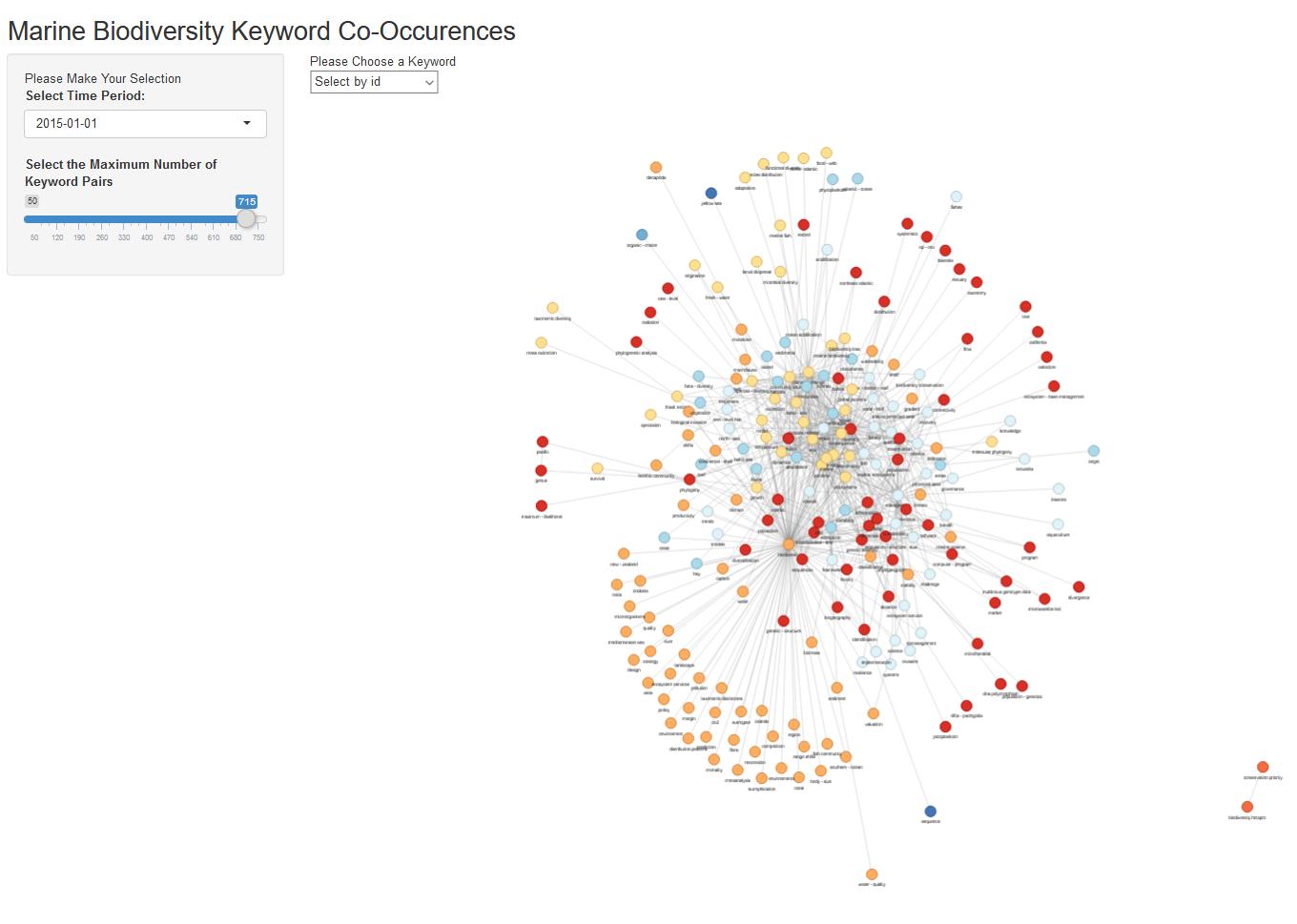

The interdisciplinary and international team of the ERC project MARIPOLDATA researches the role of science in the BBNJ negotiations through a multi- and mixed-method approach, using event ethnography at the intergovernmental conferences to collect qualitative and quantitative data, as well as bibliometric data, combined with network analysis and oral history interviews. In this way, the team maps existing marine biodiversity research and identifies collaborations on the global scale, explores the different scientific capacities of state actors in the negotiations and studies the authority of existing intergovernmental organisations within the BBNJ regime complex, portrays differences in state positions regarding key BBNJ issues and looks at case studies of specific regions within the BBNJ context. One key pillar of the MARIPOLDATA project is researching how science and knowledge influence the treaty-making process and how science-policy interrelations can be improved at different policy-making stages.

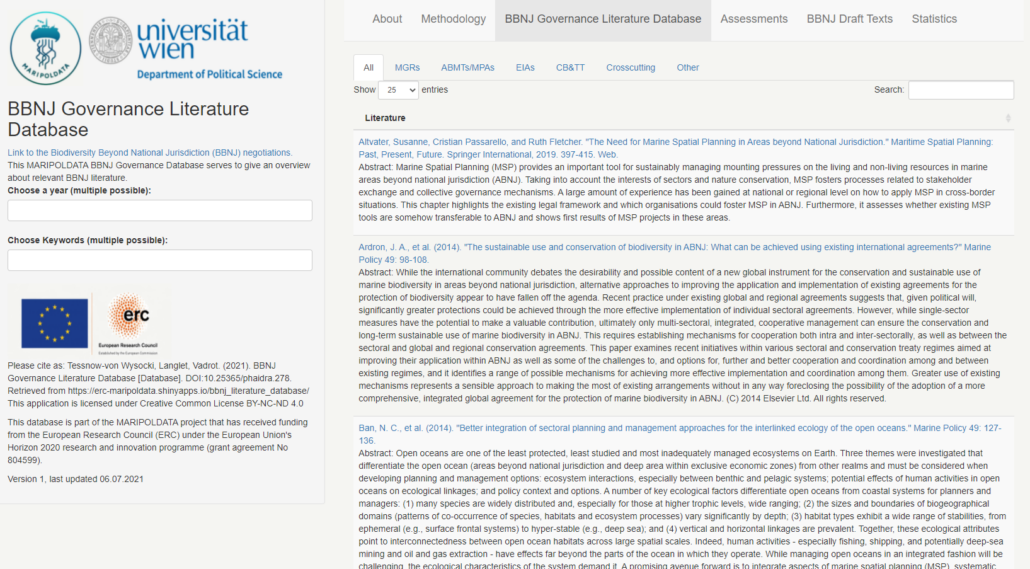

In this regard, the recently published systematic literature review serves as an up-to-date summary and analysis of scientific publications on the BBNJ process, compiling main priority topics and recommendations from 140 multidisciplinary, geographically diverse publications. Our literature review focuses on the peer-reviewed scientific findings that scholars have published on the BBNJ process. To find out what the scientific community writes about the BBNJ Agreement, we were interested in the questions: Which issues are prioritized in BBNJ research and the academic debate? Which best practices were identified and discussed in the literature that can serve as guiding principles and approaches? And what is currently missing in the debate about the future regulatory framework to protect and sustainably use marine biodiversity?

At the moment, the ongoing BBNJ negotiations have been indefinitely postponed due to the COVID-19 measures around the globe. However, informal and semi-formal online discussions continue to take place, in the form of “High Seas Online Dialogue”, organized by certain state and non-state actors, and Intersessional Work – an online platform- organized by the UN Secretariat to keep the momentum and progress towards consensus.

The time is now to approach policy-makers with the most recent scientific findings on BBNJ. At the same time, final decisions about the future of the ocean and marine biodiversity have still not been made. Within this intersessional period, there is the opportunity for recent scientific findings on BBNJ to make their way to the policy-makers’ negotiating table, and – by being put into context – to be perceived as politically relevant to be taken into consideration when negotiating the next (final) BBNJ round. In this regard, our literature review serves as a tool to untangle the complex BBNJ issues for newcomers in the field. It gives an overview of all existing work on BBNJ since the early beginnings of the process and provides insights on the latest scientific findings relevant to BBNJ.

The wave of Scientific Literature published along the BBNJ pathway

Photo credits: Lysander Yuen on Unsplash

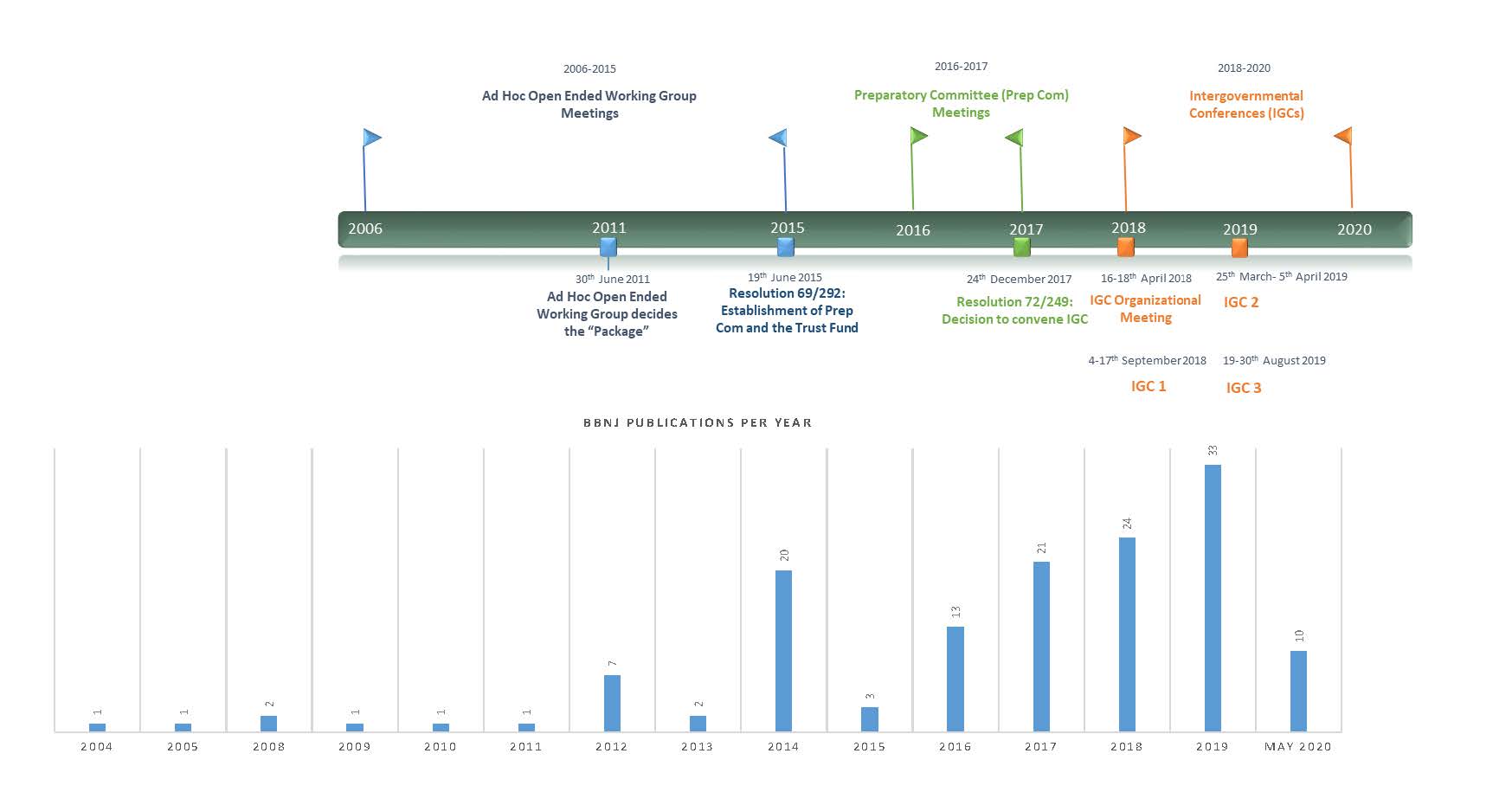

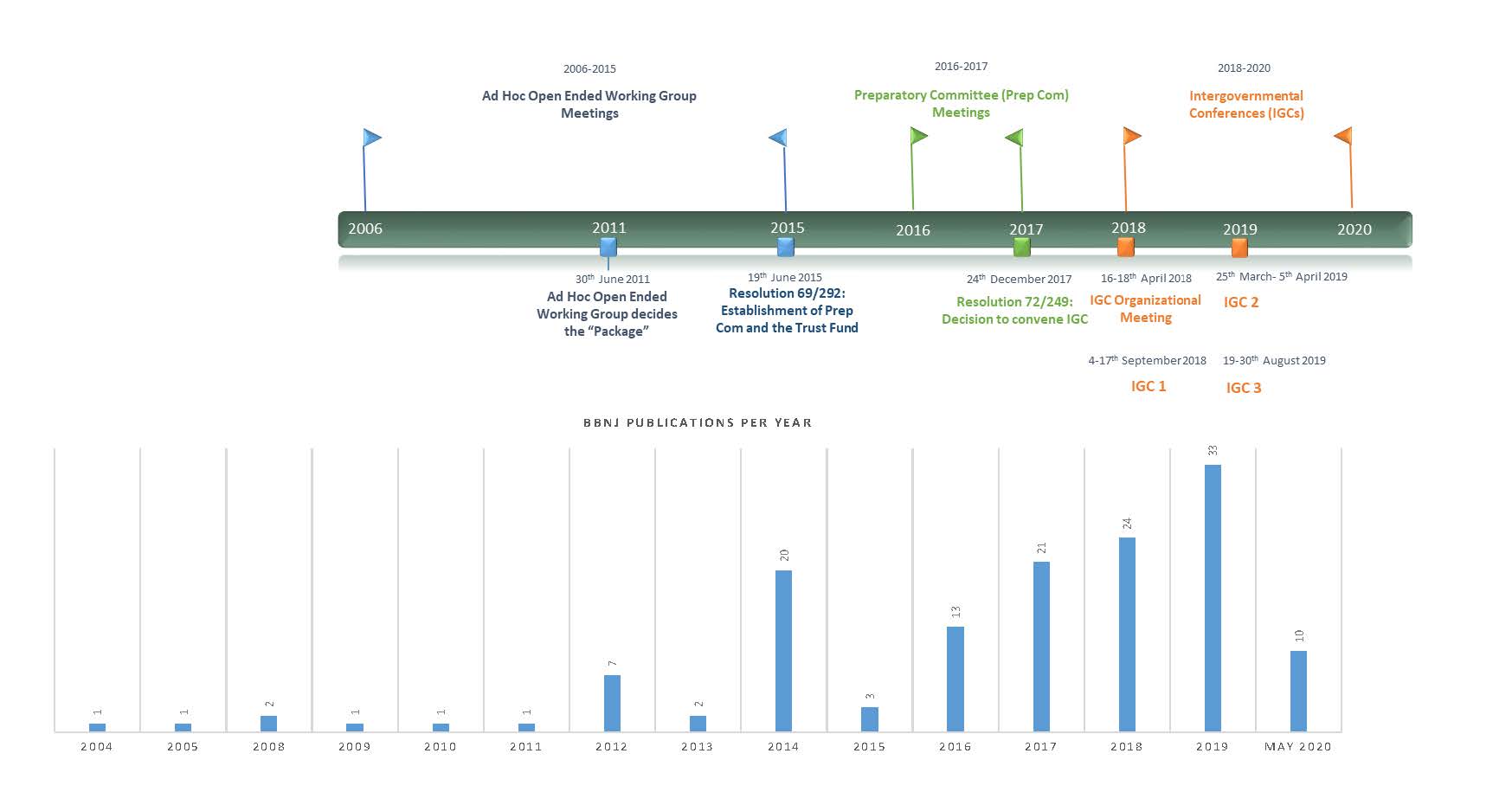

The BBNJ process started in 2006 with the first meetings of the Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal Working Group and transitioned into Preparatory Committee meetings, and finally, formal negotiations – the intergovernmental conferences, taking place in the New York UN Headquarters since 2018, which are supposed to end with the next upcoming IGC-4.

Throughout the BBNJ process, there have been many academic contributions regarding the process in the form of new scientific findings, case studies, geospatial analyses, and law reviews by authors from multiple disciplines, including oceanography, marine biology, conservation science, political science, and law. Publications on BBNJ issues and the number of new authors in this field have been growing throughout the process.

There is often little time to go through hundreds and hundreds of scientific publications, many of which are often only accessible with certain rights for academic journals and written in scientific jargon of the particular discipline. We, therefore, provide a timely overview of what is “out there” of findings, analyses, studies, and recommendations for the new agreement and critically reflect on this corpus of literature – a review intended for researchers from diverse academic disciplines in the natural and social sciences, policy-makers, and practitioners. The systematic literature review serves to capture all academic publications related to the BBNJ Treaty from the database “Web of Science,” complemented using the snowball method to include additional sources from reference lists of relevant publications[1]. The sample includes all publications referring to the BBNJ negotiations or directly relevant to the BBNJ process – since before the official start of BBNJ meetings in 2004 until 2020. More recently published articles were not analyzed in detail but mentioned in the discussion section of the review to ensure timeliness and policy-relevance for the upcoming – and planned to be last – intergovernmental conference. We observe a high increase in BBNJ publications in 2014 with a special issue on this topic, as well as a general growing BBNJ literature starting from the beginning of the Preparatory Committee in 2016. The analysis ends in May 2020, but there have been many contributions in the second half of 2020, which is expected to continue with ongoing BBNJ online discussions until the next conference and beyond.

Scientific Publications along the BBNJ Pathway

A large amount of the scientific literature we analyzed aims to directly inform the BBNJ agreement by identifying areas in need of protection, outlining consequences of certain activities on the marine environment, pointing to best practice examples and lessons learned from past experiences with international implementing agreements of UNCLOS, or other international and regional frameworks seeking to conserve or sustainably use marine species or genetic resources. Therefore, such a review is critically relevant to consider for researchers studying BBNJ, state representatives forming their positions in the negotiations, and non-state actors and civil society being involved in the process. The academic literature is valuable for scientists to make a connection to their research, serves as a knowledge base on BBNJ and is significant for policy-makers to make informed decisions about how to regulate, use and protect the marine environment for current and future generations, as well as for planet Earth in its own right.

The Voice of Science is calling

The review presents recommendations made in the scientific literature sample for each of the four package elements of the future treaty. It first examines the main challenges facing the current ocean governance framework identified in the literature and potential solutions offered by the package elements. Second, it provides for each of the BBNJ package elements: a) a compilation of scientific findings and identified priority areas, b) suggested guiding principles, approaches, and recommendations, c) references to existing law, d) best-practice examples and lessons learned and e) recommended institutional entities for implementation. Further, our review elaborates on overarching topics across package elements named by BBNJ authors, which need to be considered in the negotiations if objectives for conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity are to be met. These include ocean connectivity, the relationship between BBNJ and existing instruments, institutional design; the role of science in BBNJ; and digital technology.

Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs)

Under the existing ocean governance framework, set by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the water column of the High Seas is regulated under the “Freedom of the High Seas” principle, granting states the freedom to access and use these areas and resources under certain environmental standards. However, the seafloor in these areas is governed under the principle of the “common heritage of humankind”, guaranteeing all states an equal share of financial and other economic benefits derived from the exploration and exploitation of mineral resources. There is legal uncertainty about living marine resources, which resulted in an international debate about the regulation of their exploitation. As the access to marine genetic resources and the sharing of benefits resulting from their use (e.g. from the development of pharmaceutical products) for areas beyond national jurisdiction is not regulated under the current framework, there is a need to fill this gap with the new agreement. While the potential economic value of such MGRs remains uncertain, an increasing interest in these resources is identified in the BBNJ literature, sparking debates on the imbalance between developed and developing countries in undertaking marine research and using marine genetic resources for product development. One part of the BBNJ authors analyses and recommends ways to approach potential access and benefit-sharing systems for marine genetic resources under the new agreement, which we lay out in the literature review.

Area-based Management Tools (ABMTs),

including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

Scientists in the BBNJ literature point to the worsening state of marine biodiversity, calling into mind various harmful human activities, including climate change and other anthropogenic stressors, such as overfishing, destructive fishing practices, shipping, pollution and, the need for urgent action to reverse biodiversity loss. Within the sample of publications, valuable management recommendations can be found. Area-based management tools, including marine protected areas, are considered an important marine conservation tool by the BBNJ scientific community. As under the current ocean governance framework, there is no global responsible body for the establishment of ABMTs, including MPAs in areas beyond national jurisdiction. The BBNJ instrument offers the potential to fill this gap. Considering the ocean connectivity of various forms, recent BBNJ authors suggest new ways of thinking about area-based management tools, leaving options open to consider climate change and cumulative impacts, as well as dynamic management when designing such conservation and sustainable use tools. Marine areas, already identified as “ecologically or biologically significant” (EBSAs) could form the basis for the new establishment of High Seas ABMTs, including MPAs. Moreover, scientists identify areas in need of protection and recommend these sites for protected area establishment. An ecosystem-based approach and a representative network of MPAs are recommended for the BBNJ agreement.

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs)

Embedded in a strong legal framework, environmental impact assessments have the potential to predict, reduce and even prevent environmental harm. Within national jurisdiction, EIAs seem to be advanced; however, in areas beyond national jurisdiction, BBNJ authors see the potential for improvement. In the light of emerging activities in the marine environment, there is a need for a stronger framework to develop and implement EIAs in ABNJ, and a clear EIA process, taking climate change and cumulative impacts into account.

Capacity Building and Transfer of Marine Technology (CB&TT)

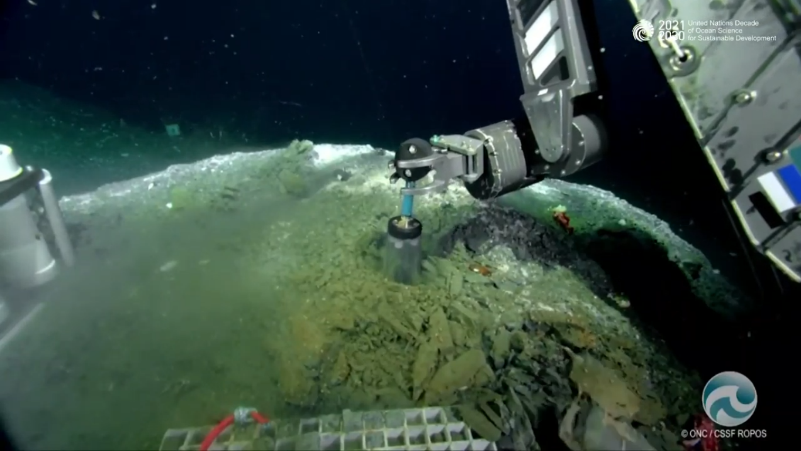

Areas beyond national jurisdiction are over 200 nautical miles (around 370 kilometres!) away from the coastlines. The deep seafloor lies several thousand meters below the ocean surface. It is obvious that to undertake marine research under these conditions, a high level of technology and equipment is necessary. Besides physical samples of MGRs, digital sequence data of these resources are of interest to research and industry. Currently, however, only a handful of countries from the Global North are undertaking exploration and exploitation of marine genetic resources and have the capacity to participate in the development of products. Academic literature on BBNJ discusses the imbalance between developed and developing countries in conducting marine research and developing products from MGRs and differences in the capacity to implement conservation measures and undertake monitoring, control and surveillance. The pillar of capacity building and transfer of marine technology is crucial to guarantee a just agreement and ensure effective implementation and enforcement.

Beyond the BBNJ package elements

Scientists from a range of disciplines writing on BBNJ issues agree: the ocean is one. Numerous interconnections have to be accounted for when discussing the exploitation of marine genetic resources, the establishment of marine protected areas and the assessment of environmental impacts. BBNJ authors explain different forms of ocean connectivity and its relevance to the BBNJ negotiations. Human activities can significantly harm marine species and whole ecosystems, but listening to science could prevent major harm. While the BBNJ scientific community is diverse, scientists consensually agree that the marine environment needs to be dealt with in precaution and be managed holistically, as a connected system. This recognizes that activity in one place of the ocean (e.g. fishing in the water column) can negatively impact other parts where the link might not be immediately obvious (e.g. impacts on the marine biodiversity on the seafloor). Also, the ocean and the climate are interlinked, meaning that changes in the marine environment can be triggered by the climate and major variation in ocean cycles can result in changes in the global climate.

Significant discussions in the literature regard how the new instrument will interplay with existing instruments and the composition of the new BBNJ instrument with its internal arrangements. The literature provides an explanation of the three institutional models that have been envisaged for BBNJ within existing mechanisms and organisations, namely Regional, Hybrid and Global and analyses specific examples of relationships between BBNJ and existing instruments. One part of the BBNJ authors provides analyses of possible institutional arrangements, including a Conference of the Parties (COP), a Scientific and Technical Body, a clearing-house mechanism (CHM), and a financial mechanism, as well as provide ideas for implementation and compliance of the agreement.

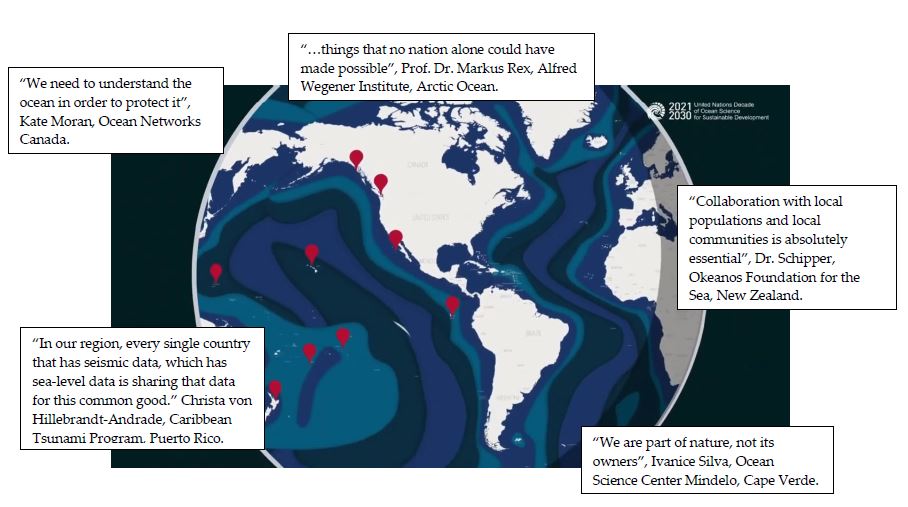

Science plays a crucial role in all BBNJ package elements. Knowledge on the ocean and its ecosystems is necessary to understand the world’s ecosystems and use the ocean’s resources for product development in the pharmaceutical, biofuel, and chemical industries and to protect marine biodiversity. Some BBNJ authors emphasize the need for scientific cooperation in BBNJ, coupled with capacity building and marine technology transfer. There seems to be a general agreement that science is needed in the decision-making process. Still, there is no universal definition of the knowledge forms and no consensus on what tasks and powers would be appropriate for a scientific and technical body. Some BBNJ authors provide best practice examples and lessons learnt from existing science-policy interfaces in ocean governance institutions.

Another part of the BBNJ literature regards the overarching theme “digital technology”. It is identified as important to develop products from MGRs using digital sequence data. Moreover, it also contributes to the conservation of species through understanding migratory routes. Satellite data can support the identification of mobile MPAs, as suggested recently by some BBNJ authors.

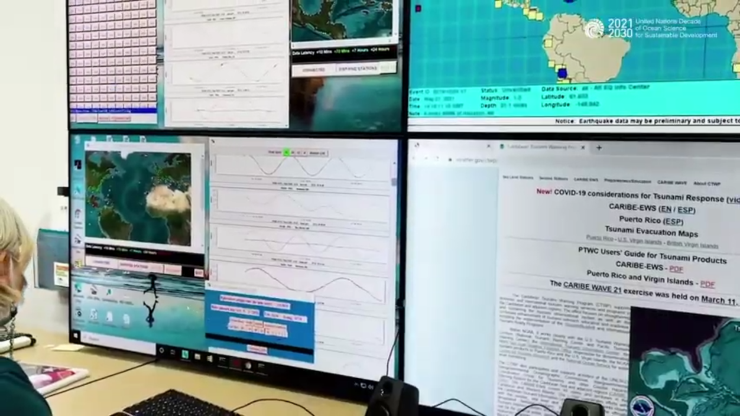

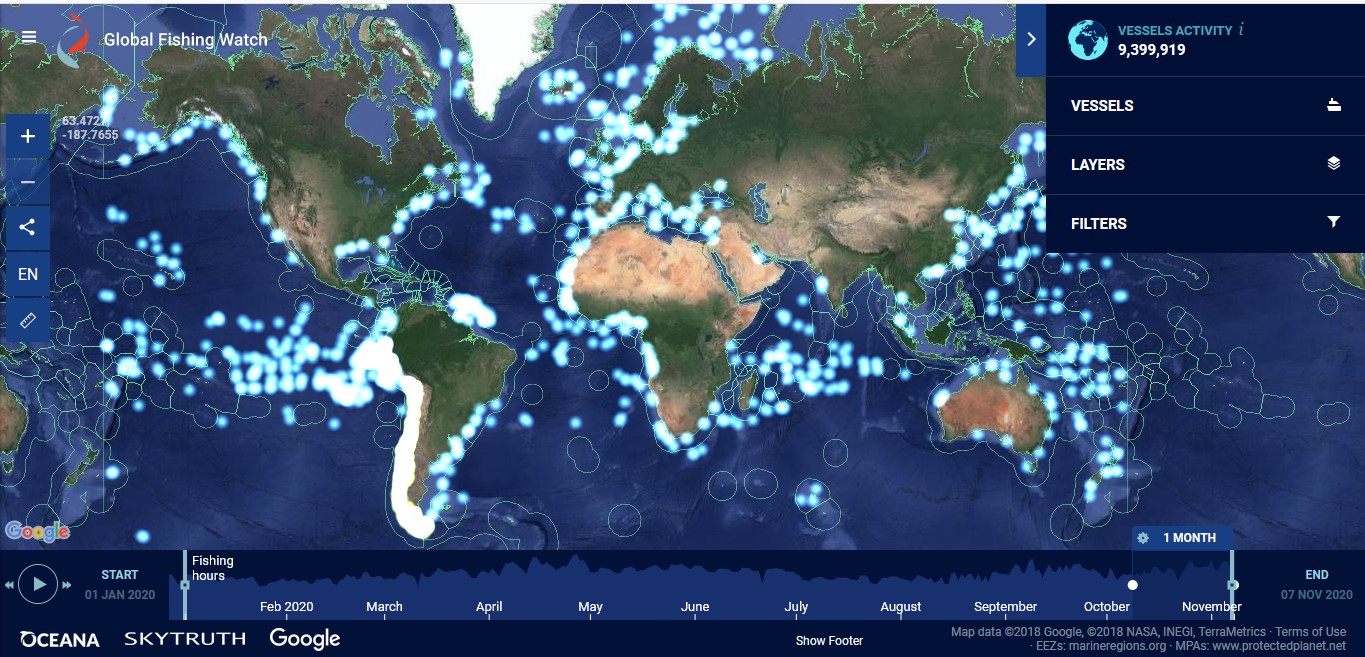

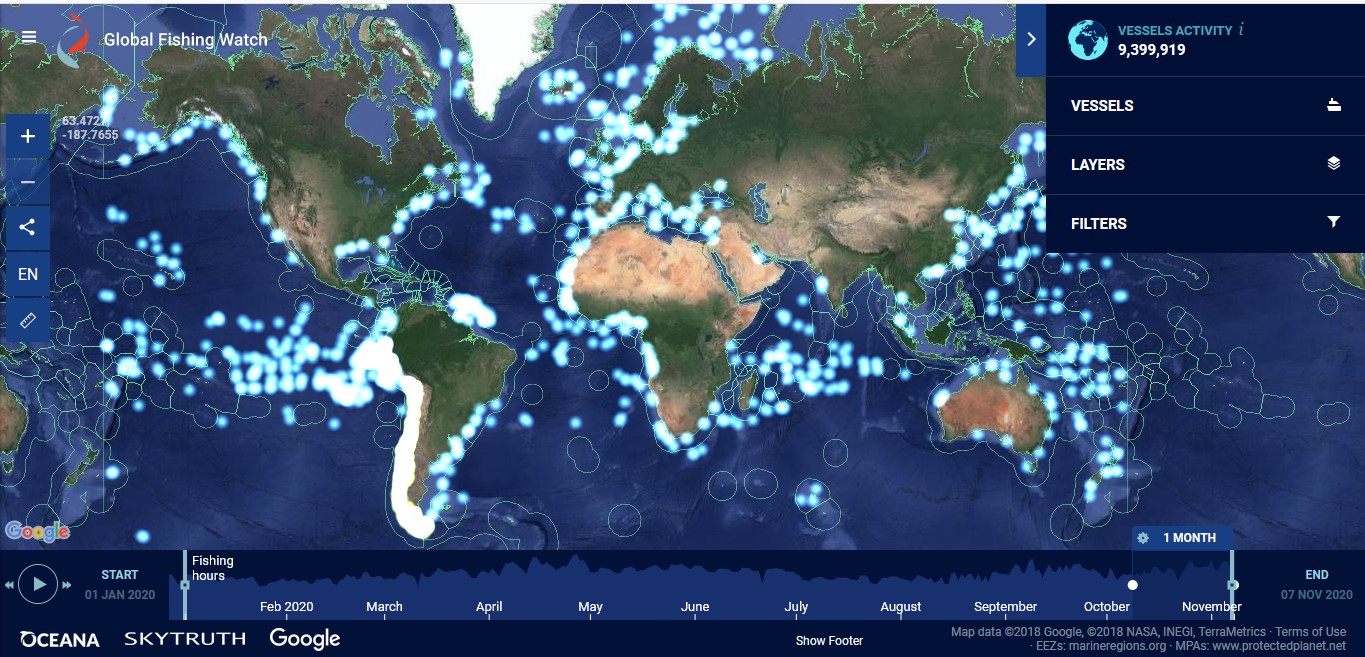

Furthermore, monitoring, control and surveillance measures can significantly be improved through automatic identification system (AIS) which uses satellites to transmit real-time data of fishing vessels’ location. Such technology is particularly helpful in ABNJ, as these areas are largely remote and not easily accessible for physical monitoring. The NGO Global Fishing Watch is using such technology to track global fishing activities in real-time.

Photo credits: Global Fishing Watch

Will BBNJ blow a wind of change against the stormy sea?

As responsible policy-makers, researchers, civil society actors and parts of the private sector- with this knowledge – we can no longer continue the “business as usual” but need to be open to alternative forms of living in harmony with nature. Based on the review, we identify two important gaps in the BBNJ literature that need to be addressed if we are to conserve marine biodiversity in international waters: the science-policy interfaces and the need for transformative change.

The need to consider science in the ongoing BBNJ negotiations to conserve and sustainably use the ocean effectively does not seem to be disputed by many, however, how such interaction between science and policy takes place is not sufficiently studied. Ways through which science and knowledge reach policy-makers and under what conditions such findings impact the negotiations are yet to be identified. Formalized processes are required to guide the integration of science and other forms of knowledge, including local and traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. Moreover, an independent expert body for BBNJ, which is currently discussed at the BBNJ negotiations, is necessary to implement the treaty’s targets successfully.

Need for transformative change

To understand the roots of the anthropogenic threats to the ocean, social, political and economic factors need to be considered. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) recognized that biodiversity loss could only be reversed by introducing transformative change into our societies. Such debate is not (yet?) visible in the BBNJ context, but is important to reflect on when seeking to conserve and sustainably use the ocean. Existing economic, political and social structures have led to the dramatic state in which the ocean is now. Reversing such damage, thus, requires to re-think the “business as usual” and imagine alternatives.

There is a need to uncover the politics behind tensions in the negotiations, including competing environmental values and legitimate knowledge. In the light of negotiating global commons, we need to examine if the existing structures ensure adequate representation of the international community and consider the idea to represent future generations and nature in itself. With our critical view on the corpus of BBNJ literature and the identification of gaps, we encourage to develop ideas and ways forward – without taking the “business as usual” within existing political, economic and social boundaries as a given – and to think beyond such structures for creating new regulations for marine biodiversity that serves all of humanity and contributes to a healthy ocean for its own right.

Open Access to full article: Tessnow-von Wysocki, I. and Vadrot, A. 2020. The Voice of Science on Marine Biodiversity Negotiations: A Systematic Literature Review. Frontiers in Marine Science 7: 614282.

Past MARIPOLDATA blogs about the BBNJ negotiations:

Key findings from our study of the marine biodiversity field and why our data matters for the new BBNJ treaty by Alice Vadrot and Petro Tolochko, December 22, 2020

Slow progress in the third BBNJ meeting: Negotiations are moving – but sideways, by Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki on September 6, 2019

Setting the stage for the common heritage of humankind principle: Diving into further negotiations on a new marine biodiversity treaty, by Alice Vadrot, Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki and Arne Langlet on August 28, 2019

Impressions from the second week of BBNJ negotiations and why they became political in the end, by Alice Vadrot and Arne Langlet on April 15, 2019