A new Marine Biodiversity Treaty in Sight

Finding a landing zone for BBNJ. Photo: Pixabay

A new Marine Biodiversity Treaty in Sight

Marine Biodiversity Negotiations have resumed in New York and negotiators are left with one more week to finalize the new treaty which will govern conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). The MARIPOLDATA Team has been following the proceedings closely. This blog follows the BBNJ Blog Series and provides an overview of the progress of the first week and outstanding issues, which still need to be resolved in the days to come.

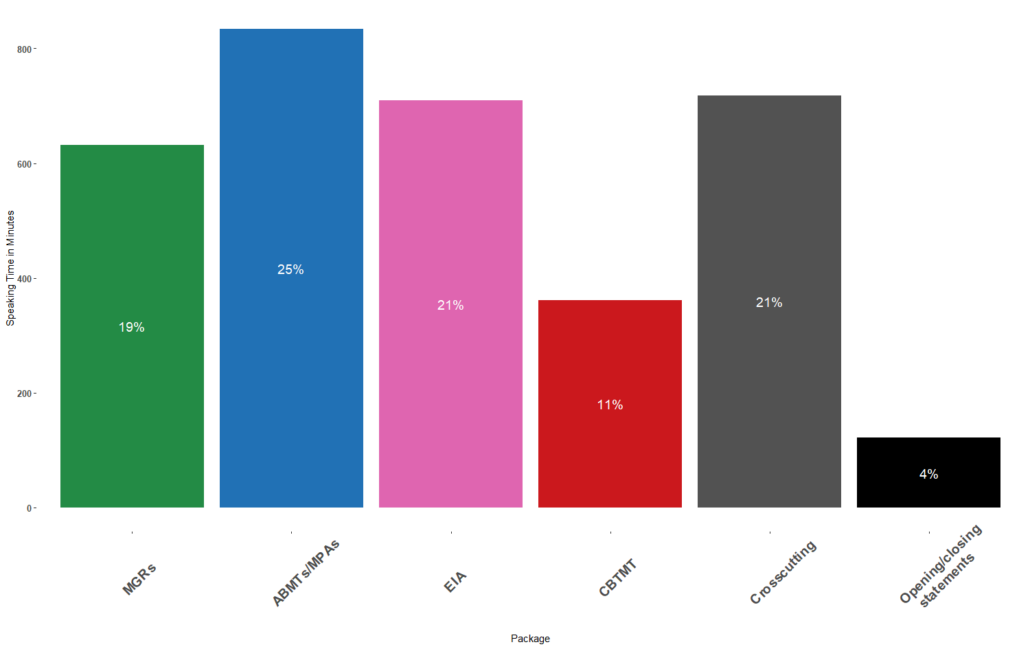

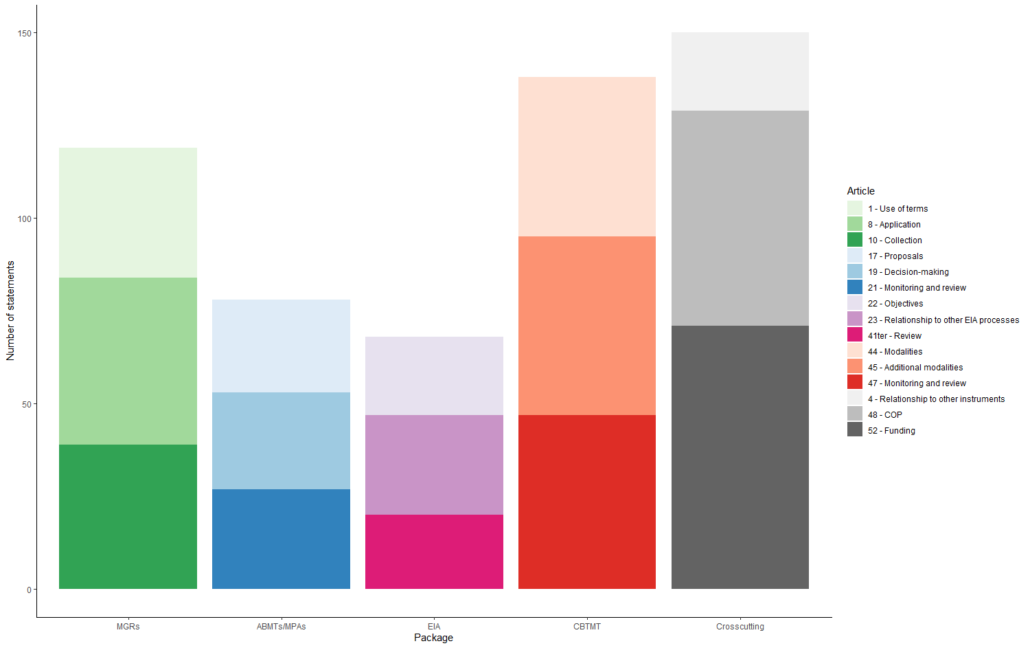

The week was characterized by ups and downs in the different sessions that were covering the package elements Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), Area-based Management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and Capacity Building and the Transfer of Marine Technology (CBTMT), as well as overarching “Cross-cutting Issues”. The latter includes provisions on general principles and approaches governing the new instrument, the institutional setup regarding the decision-making organ (Conference of the Parties (COP)), the Scientific and Technical Body, the Secretariat, and the Implementation and Compliance Committee. Overall, the first week was characterized by a spirit of compromise by Parties, gradually finding a “landing zone” – namely agreement – on various contentious issues.

Final drafting of the new treaty

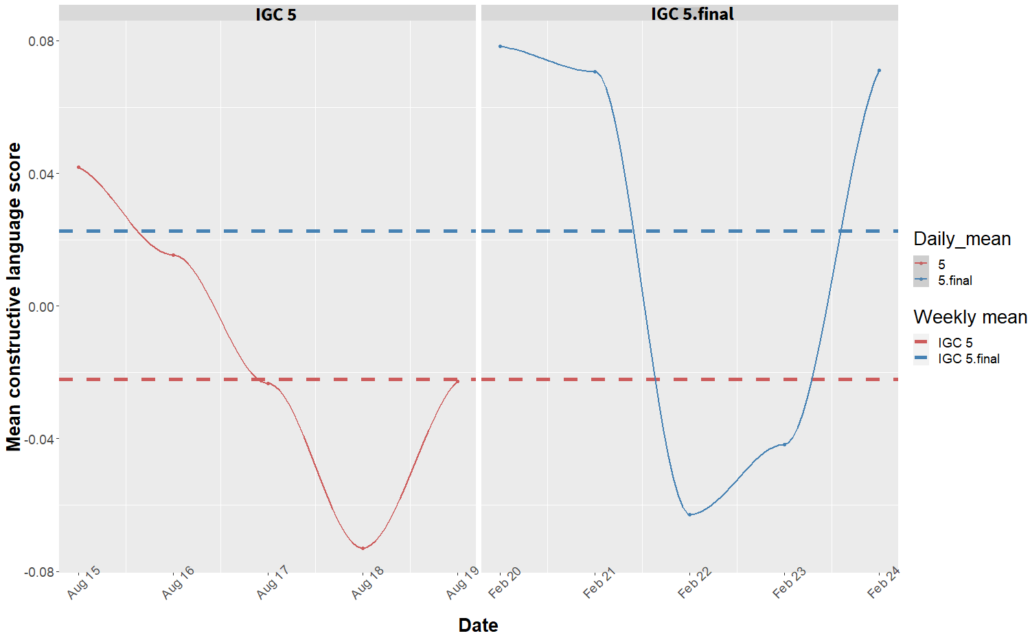

Throughout the first week, negotiations were advancing at different paces on different topics, leaving the issues of firstly, fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of marine genetic resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction and secondly, the establishment of ABMT, including MPAs as the most challenging parts. Compared to the last conference session in August, the section on EIAs went surprisingly fast, with much flexibility from State Parties and proposals for compromise. Also regarding CBTMT, the textual drafting proceeded without substantial conflicts. The hope that negotiations are now in the final days before the adoption of the agreement can be derived from the language that States use in engaging with each other’s positions and arguments. States’s statements showed that they are willing to work together constructively and with the necessary flexibility.

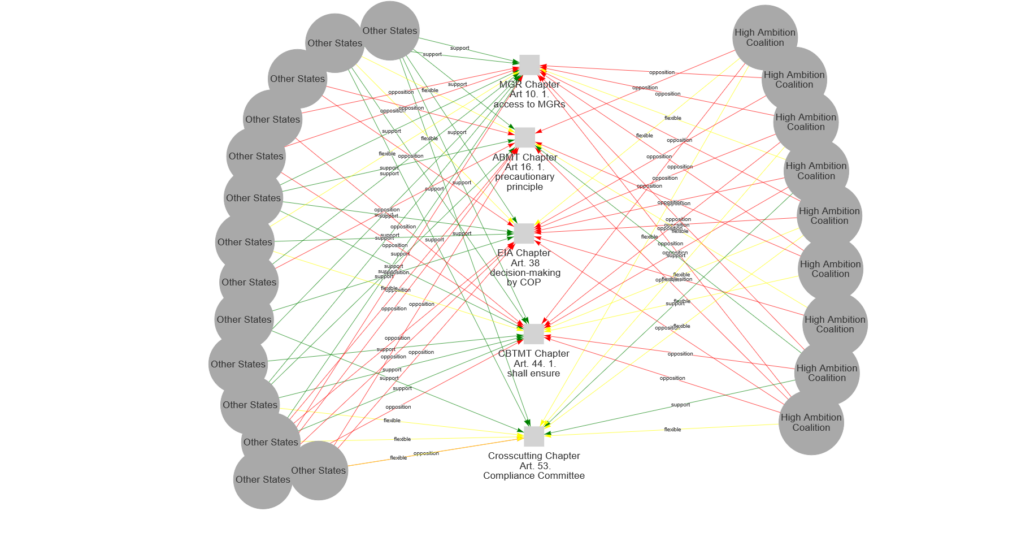

Figure 1: Language analysis of constructiveness of States’ statements

Using our notes from State Parties’ interventions in the plenary and informal informal sessions, we ran a latent semantic scaling language model to evaluate how constructive the language of the negotiators’ statements was. The language used by States is an important indicator for how a negotiation is progressing (Georgiadou, Angelopoulos,and Drake 2020). We see that in the first week at the resumed 5th session “IGC 5.final”, States used more constructive language than during the same time period at IGC 5. State Parties formulated their statements in a particularly constructive manner at the end of week 1, compared to the previous round of negotiations in August.

Marine Genetic Resources

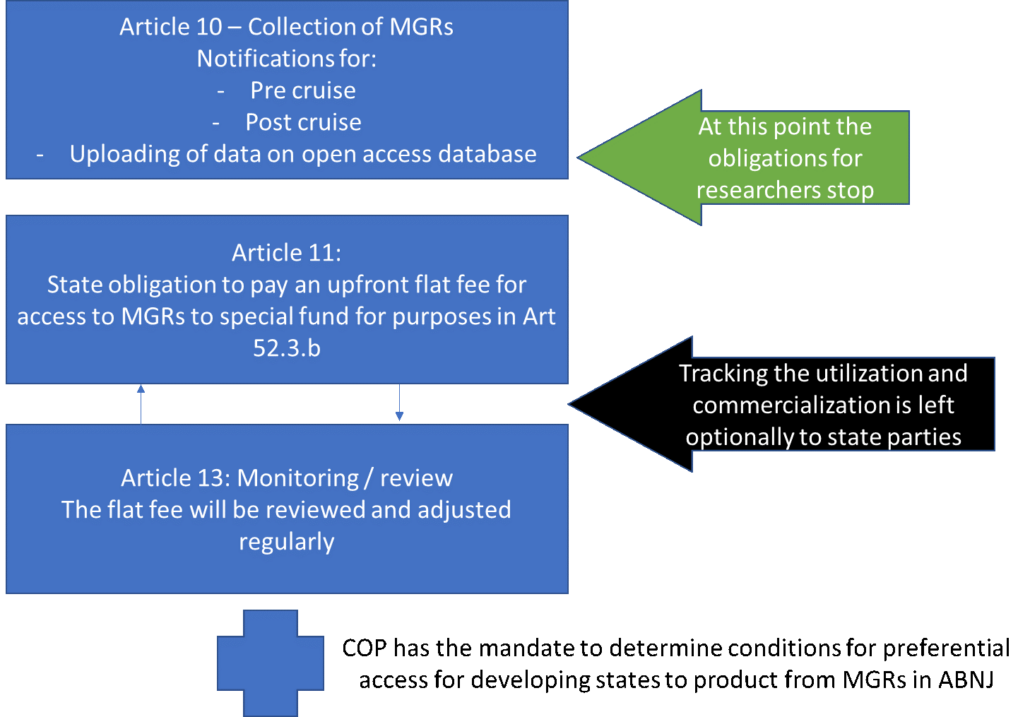

The discussions on MGRs started on Monday with two new written proposals from developing and developed State Parties. This promised a constructive and engaged start – a lack of written proposals reflecting the ongoing discussions hampered progress during IGC 5 in August 2022. The proposals made big steps towards compromise as they both converged on an obligation for monetary benefit sharing through an upfront payment. Both sides offered significant concessions from their initial pre-IGC 5 positions to get to this point: developed States moved away from their complete opposition to any sort of monetary benefit sharing and developing States in turn accepted that such monetary contributions are purposed for achieving the objectives of this treaty (conservation and sustainable use). Such a spirit of comprise will be needed to resolve the remaining issues.

Substantial differences remain on whether upfront payments shall be accompanied by a so-called “enabling clause” or an obligation for payments based on the commercialization of MGR-related products. An enabling clause would mean that obligatory payments on commercialization would not form part of the initial agreement, but that the COP would deal with the matter and possibly develop modalities for such payments. The envisioned enabling clause opens the possibility of commercialization-dependent payments without specifying details at this stage. However, the enabling clause as currently proposed leaves too much uncertainty on whether it will ever be invoked, as it requires consensus from all State parties.

A similar difference emerged over the long-standing debate on how to treat digital sequence information (DSI). Again, one side offered an enabling clause and the other side requested clear commitments. Both sides had in mind the recent decision by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) COP on the inclusion of DSI for benefit sharing in their lines of argumentation. Developed countries preferred to leave this issue open, waiting for the “fair, transparent, inclusive, participatory and time-bound process to further develop and operationalize the mechanism” (CBD, COP decision 15/9, Art. 17) whereas the developing states insisted that “the benefits from the use of digital sequence information on genetic resources should be shared fairly and equitably (CBD COP decision 15/9, Art. 2) and wished for this to be clarified under the BBNJ regime as well. The compromise may lie in the level of details, as the regime needs to a) accomplish legal certainty for developing states that benefits from DSI will be included and b) remain flexible to take up developments occurring under the CBD mechanism.

It was noted that it would help developed States in the ratification process if reasonable and doable obligations on State parties are clearly stated throughout Part II of the agreement. In terms of the notification mechanism, a realistic landing zone may lie in requiring State parties to ensure the use of standardized identifiers and regular aggregated utilization reports from databases.

States agreed that some sort of access and benefit-sharing body will be established to overview and inform implementation of this part. The initial proposal to have a “mechanism” appears to draw logic from the “mechanism” established under CBD. Suggestions to replace this wording with “advisory committee” were met with the argument that all subsidiary bodies established under the instrument will be advisory to the COP and hence, this needs not to be explicitly stated for this body only (see MARIPOLDATA blog on marine issues and DSI at CBD COP15.2).

Area-based Management Tools, including Marine Protected Areas

While the discussion on whether to have consensus-based decision-making in the COP for establishing the new ABMTs/MPAs is still on the table, most States prefer a majority-based voting procedure. This would mean that proposed ABMTs/MPAs cannot be vetoed by one Party alone, if the majority of the international community agrees on the necessity to undertake this new measure to conserve and sustainably use marine biodiversity. Linked to this discussion is the question of so-called “opt-out”, meaning a State Party objecting to the establishment of the new measure can “opt out” of their obligations to comply with the measures (On the delicate balance between opt-outs and majority voting in other instruments see recent IISD guest article). As explained in previous MARIPOLDATA blogs, this risks having States as Parties to the agreement without actually complying with what is agreed by all or by a majority of the COP, threatening the effectiveness of such measures. Throughout the negotiations, and in the spirit of compromise, there is acknowledgement that this agreement will not fully meet one single State’s interest but rather, that it needs to be a compromise solution that works for all and improves the current situation on the high seas. Under this premise, many States have moved away from their original preference of not having the “opt-out” clause, but rather putting in place a majority vote in the COP and – in very special cases – allow for such exemptions. The following days will be crucial in negotiating the knitty-gritty of the legal text to close loopholes and at the same time allow for universal participation of States to the BBNJ treaty.

The second issue is how the new agreement will account for “other relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies” (IFBs) that are already in place and ABMTs that are already established – or will be established – by those bodies and frameworks. Some Parties interpreted the wording in the draft text as an introduction of a hierarchy between recognized and unrecognized ABMTs/MPAs by the BBNJ instrument, which would neither be possible nor desired in international ocean governance. The coming days will be busy with finding the right wording to agree on the cooperation and coordination of BBNJ with existing International Frameworks and Bodies (IFBs) with the aim to enable coherent biodiversity governance of ABMTs/MPAs, facilitating well-connected networks of ABMTs/MPAs in areas beyond national jurisdiction (this covers the water column and the seafloor but is currently governed by different international regimes). In the light of ecological connectivity – the knowledge of ecological, biological, genetic and cultural interconnections – such joint establishment of ABMTs/MPAs among the different governing bodies is crucial for effective conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity (Tessnow-von Wysocki & Vadrot, 2022) (see: MARIPOLDATA blog on marine issues and DSI at CBD COP15.2).

Towards the end of the first week, discussions were again taken up on issues that were believed to have been resolved already in the past conference session, such as definitions of MPAs, and threatened to throw the negotiations back to where they had left off in August.

Environmental Impact Assessments

The part on EIAs advanced comparatively quickly on passages of the text that were unresolved from the last conference session, due to constructive compromise proposals by several regional groups, which took into account concerns of State Parties that were raised during the past years of negotiation.

The discussions seem to evolve into a two-tiered approach for EIAs between a complete unilateral decision-making over activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction and a full COP decision-making. Several layers of such internationalization at different steps of the EIA process still need to be formulated but both sides seem to converge on a possible “landing zone” and middle ground between the contrasting concepts. In this way, the disagreement about an effects vs. location-based approach could be advanced. Some controversial issues, however, still remain. At one point, the facilitator even felt that “we are rowing backwards”.

Details of a “call-in” mechanism will still need to be finalized in the coming days, ensuring a process to question a screening undertaken by one Party that would allow the activity to be conducted without an EIA. One particularly contentious issue is the inclusion of a set of guidelines or standards to which the EIAs need to be upheld – as in the current discussions it would be the State Party itself who is undertaking an EIA for their own planned activities. Discussions on whether additionally to voluntary guidelines, this new legally binding agreement should also provide minimum universal standards that all States need to follow when conducting their EIAs. This is still a highly controversial topic and remains to be discussed until the last days.

Another issue regards the key question when an EIA will need to be undertaken. In this discussion, two different thresholds on the table would trigger an EIA: 1) significant and harmful changes and 2) minor or transitory effects to the marine environment. This issue has been avoided in discussions, as no easy compromise is expected in this regard. The same attitude was observed for the role of the Scientific and Technical Body, which was left to the very end of week one.

Capacity Building and Transfer of Marine Technology

From the beginning of IGC 5.final, the CBTMT negotiations proceeded relatively smoothly and in clear view on compromise. In the first session, the two State groups holding different views on the topic called the draft text a “clear” and “well balanced” document that “has realistic landing zones”. It was, for example, encouraging to observe that the differences around “shall ensure” in Art. 44 were largely resolved and the wording of the text accepted.

Disagreement emerged over the proposed addition of the “term” financial to the list of capabilities that shall be enhanced under Art. 46.1. Whereas developing states referred to the required commitment to financial support for capacity-building, developed states argued that the term financial does not fit in the logic of the paragraph. Related to the developments under the MGRs chapter, these differences can certainly be settled by providing the necessary legal certainty and commitment for developing countries that financial support for capacity building is given.

Unsettled cross-cutting issues

Under Cross-cutting issues, States discussed which principles and approaches should guide the new instrument in two informal-informals sessions. This section of the agreement has been difficult to discuss and left a few concepts up to debate that will form the basis for the new treaty. Negotiations circled back to previous discussions on precautionary principle/approach or the newly phrased term ‘application of precaution’ with a general agreement that the latter could not be a good compromise and would result in further questions of how to define and apply in practice. Developing States pointed to the large number of countries of regional groups to convey their arguments for the precautionary principle. Yet, whether to use the precautionary principle or approach remains to be discussed.

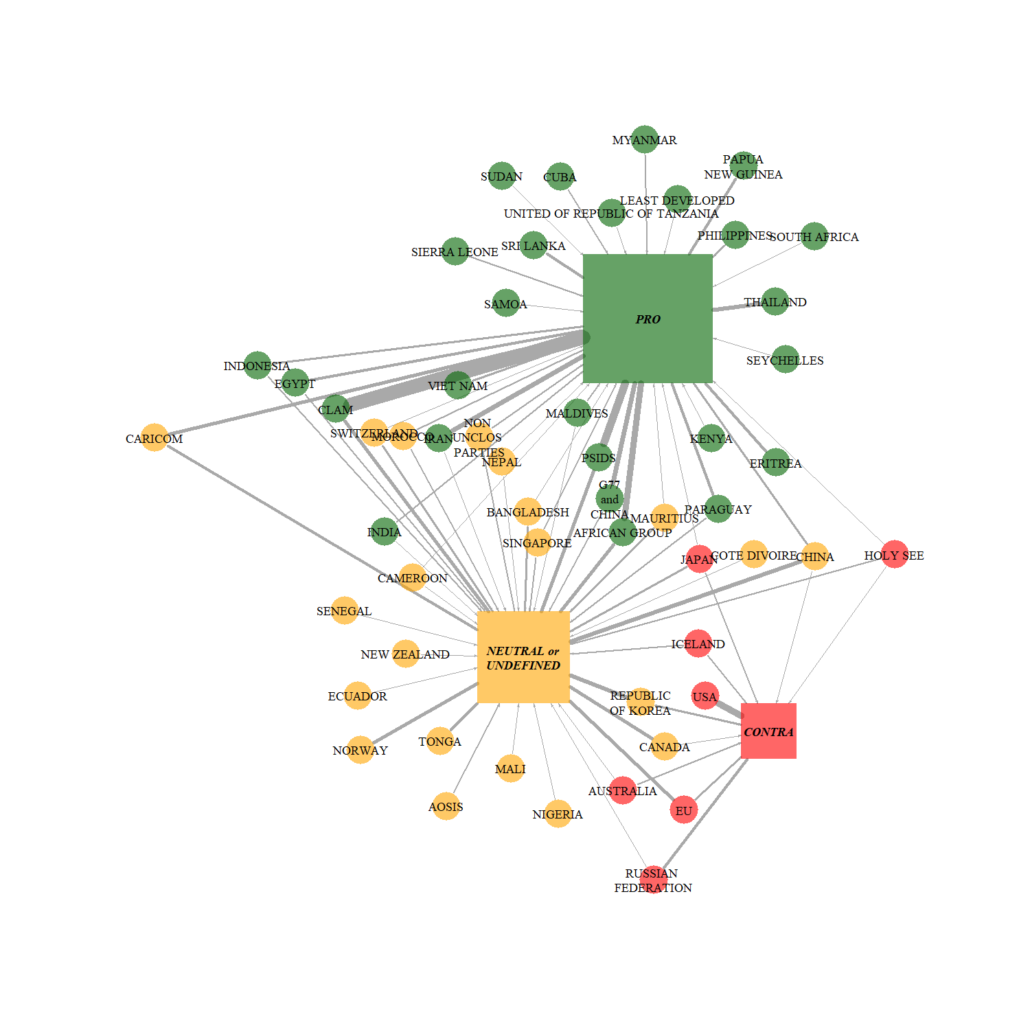

Also, the option of including the principle of common heritage of humankind as a guiding principle meets much controversy, similar to previous negotiations. It remains to be seen how this disagreement can be resolved to satisfy both proponents of the 1) principle of the common heritage of humankind (mostly developing states) and 2) freedom of the high seas (mostly developed States). In the spirit of compromise, we wonder if a principle encompassing the benefit for the planet could resolve the opposition of two historical principles and provide the basis for the mandate of the BBNJ treaty focusing overconservation and sustainable use (see: MARIPOLDATA blog on common heritage of the planet).

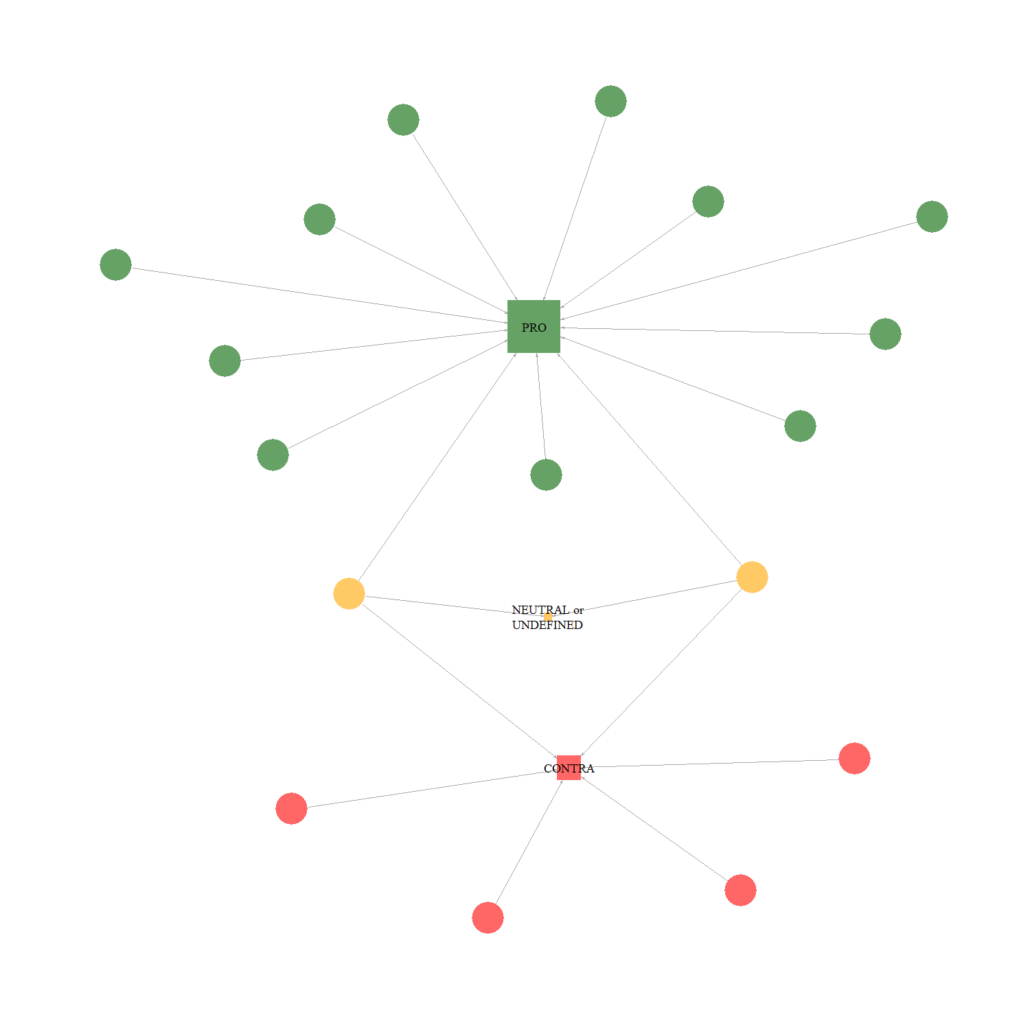

Figure 2: State (and state-group) positions on whether to include the common heritage of mankind in Art. 5 on general principles and approaches – visualized to depict the conflict over the common heritage principle (position in squares, States in circles).

|

|

| Conflict over Common Heritage of Mankind,

IGC 2 & 3 Source: Vadrot et al., 2021 |

Conflict over Common Heritage of Mankind,

IGC 5.final Source: Authors |

Another important topic under cross-cutting issues is the future relationship of the BBNJ instrument with other bodies. Considering the already existing amount of international organizations and regimes and the resulting complexity of marine governance, there is the real risk that a strict not undermining clause (Art. 4.2.) may result in little transformative possibility. Proposals to reformulate Art 4.2. that focused on the effectiveness of measures of the instruments were rejected. During the first week, States concerned that BBNJ may turn out too weak instrument provided a new proposal to strengthen the BBNJ instrument. The text now contains two brackets to “respect the competences of” and to promote “mutual support”, which would reflect the bidirectional relationship of the not-undermining issue (See MARIPOLDATA blog on the relationship with other instruments and organizations). The future of these brackets remains to be seen in week 2.

On another previously contentious issue – Art. 52 on funding – a road to compromise is visible. The stronger language “shall provide for” (own emphasis) has become acceptable to most States when the qualifier “in accordance with its national policies, priorities, plans and programmes” is added to the end of the sentence.

A completely new discussion started around the wording “indigenous peoples” which was capitalized (“Indigenous Peoples”) in the most recent draft text. A number of countries expressed their opposition to this change which for them represents more than a mere editorial drafting change. Countries in favor of the capitalization argued that capitalization followed a precedent and current UN practice in drafting official documents. The editorial capitalization was retained in the new draft text of February 25 but a small working group was set up to solve this issue throughout all provisions of this agreement.

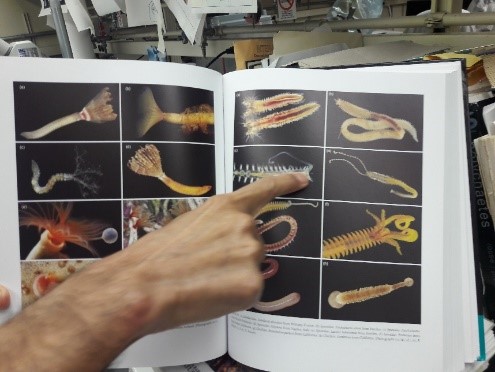

The “fluffy beast” and other institutional arrangements

A very fluffy Beast. Photo: Pixabay

Discussions evolved around the details of an Implementation and Compliance Committee to ensure the effective operationalization of the treaty obligations. As pointed out during the discussions, such a committee will probably rather be a “fluffy beast”, with a non-adversarial and non-punitive character and no real legal sanction case of non-compliance. Still, it was agreed on the importance of such a committee to assist States in their implementation of treaty obligations and, thus, a key institutional arrangement for meeting the treaty’s objectives. Moreover, no consensus has been found on dispute settlement, keeping the divide between Parties and non-Parties to UNCLOS.

Another important institutional arrangement to meet the treaty’s objectives will be the Scientific and Technical Body (STB) and related questions about how scientific advice will flow into the implementation of the BBNJ treaty. While the provision on the STB in Art. 49 was agreed on fairly quickly, modalities and character of such a body remain to be developed by the COP at a later stage. In the specific parts of the agreement dealing with the future role of the STB, there was no easy compromise on the role of this body. Pending discussions include the role of the STB in consultations on and assessment of proposals for ABMTs/MPAs, some sort of oversight of the STB regarding decisions by Parties that screenings or EIAs will not be necessary, it’s involvement in the “call-in mechanism”, and consequential actions that would need to be required in response to the recommendations of the STB. Moreover, a potential role for the STB in assisting EIA processes of States with capacity constraints and in the conduct of further public consultation is being discussed. A potential role of the STB in reviewing, proposing rectifications to and publishing EIA (draft) reports is considered by Parties. Regarding decision-making on whether a planned activity can be carried out, the STB could play a role in reviewing EIA reports prior to authorization of an activity and review reports on the impacts of authorized activities to make recommendations on whether the activity should continue.

As regards the Conference of the Parties (COP), discussions have not been exhausted on whether the COP will take decisions by consensus or majority vote, and if so, which majority. Moreover, it was agreed that there should be regular meetings, however, how often and where such meetings will take place are still up for negotiation.

In negotiations on the Secretariat, Parties seem to agree on the need for a separate Secretariat apart from UNDOALOS. Which country may host a separate Secretariat is however still up to debate.

Compromising on the future Treaty

Now it will be crucial to see which topics can be agreed on and included in the legally-binding agreement – and which decisions will be left to the COP to decide in future meetings (which then will not be able to gain mandatory character without amendments to the agreement). The final text will need to be ready mid-week in order for the legal drafting committee to give the final touch and have it translated into all official UN languages in time for adoption before negotiators leave to return to their home countries. Reasons to hope for a successful conclusion of the agreement exist: The good work of the secretariat in providing a new comprehensive draft text is a major step. As promised by the president during the plenary on Friday morning, a new text was released “Saturday during daylight” for negotiators to continue bilateral meetings over the weekend.

References:

Georgiadou, Elena, Spyros Angelopoulos, and Helen Drake. 2020. “Big Data Analytics and International Negotiations: Sentiment Analysis of Brexit Negotiating Outcomes.” International Journal of Information Management 51: 102048.

Tessnow-von Wysocki, Ina., & Vadrot, Alice B. M. 2022. “Governing a Divided Ocean: The Transformative Power of Ecological Connectivity in the BBNJ negotiations”. Politics and governance, 10, 28. doi:10.17645/pag.v10i3.5428

Vadrot, Alice B.M. Langlet, Arne. Tessnow-von Wysocki, Ina. 2022. “Who owns marine biodiversity? Contesting the world order through the `common heritage of humankind´ principle”. Environmental Politics 31(2): 226-250

Watanabe, Kohei. 2021. “Latent Semantic Scaling: A Semisupervised Text Analysis Technique for New Domains and Languages.” Communication Methods and Measures 15 (2): 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1832976.

Watanabe, Kohei. 2023. “Introduction to LSX, the Package for Latent Semantic Scaling.” http://koheiw.github.io/LSX/articles/pkgdown/.