Next steps to implement the BBNJ Agreement through capacity building and technology transfer

Written by Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki, Fuad Bateh, Judith Gobin, Harriet Harden-Davies, Kwaku Kyeremeh & Julia Schutz-Veiga

Only a few months after the adoption of the new legally binding agreement on biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ) in June 2023, stakeholders gathered for the BBNJ Symposium in Edinburgh on October 6-7th. The Symposium brought together experts from policy, science, conservation and the private sector to discuss the first steps towards implementation and to deliberate on yet unresolved issues. The calls for a Preparatory Commission were followed through by the United Nations Assembly Resolution in April 2024, with the first organizational meeting taking place from 24-26th June, 2024. This blog focuses on how capacity building and the transfer of technology (CBTMT) were discussed during the Symposium and reflects on equity issues in BBNJ and opportunities for action prior to entry into force of the agreement.

Closing the capacity gap with the BBNJ agreement. (Source: Unsplash)

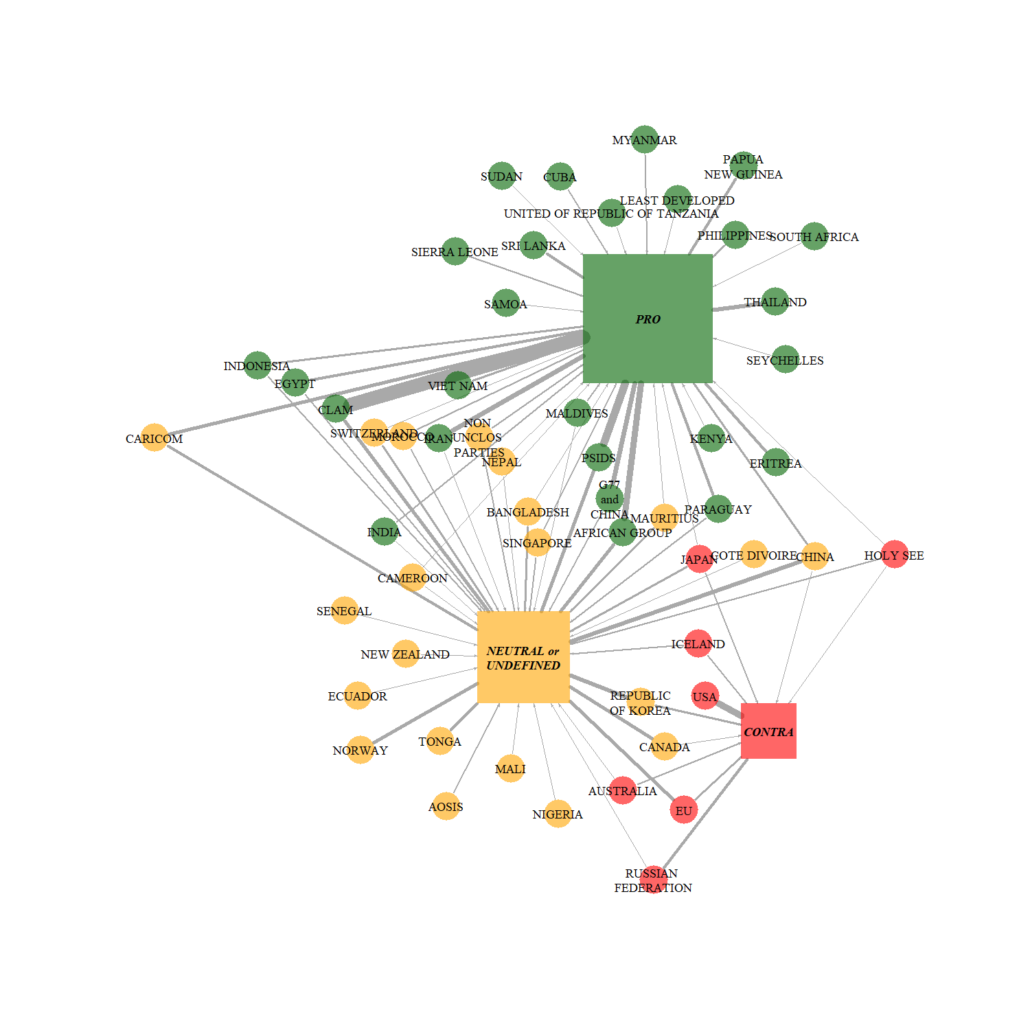

With the adoption of the new marine biodiversity agreement, a milestone has been reached. After nearly two decades of deliberations, the United Nations have agreed on a legally binding instrument to govern the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. The new agreement falls within the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), as a new implementation agreement. States quickly signed the agreement, already counting 91 signatories after the final adoption session in June 2023. Yet, to enter into force, the BBNJ agreement will require 60 ratifications, only seven of which have been formally deposited to the UN (Palau, Chile, Belize, Monaco, Mauritius, Federated States of Micronesia, Seychelles) (UNCLOS, 2023).

Formal ratification, which in many cases includes adjustments of national laws or processes is the first step towards entry into force. However, successful implementation of the agreement goes beyond signature and ratification: Successful implementation of the BBNJ agreement will need a long-lasting strong capacity building element for States that currently lack the necessary information as well as scientific and technical capacity to conduct studies on the marine environment and fully implement the new instrument. The BBNJ agreement acknowledges this by having introduced capacity building and the transfer of marine technology as one main pillar of the new instrument (BBNJ Agreement, Part V). The inclusion of CBTMT into the agreed BBNJ package of topics in 2011 goes also to the broad perception that CBTMT is one of the most under-fulfilled aspects of UNCLOS, but key to implementation (Lothian, 2022). This blog maps out main findings from the expert panel on capacity building and the transfer of marine technology at the BBNJ symposium session to help implement the BBNJ agreement in an efficient and timely manner and reflects on the way forward.

Expert Panel on CBTMT

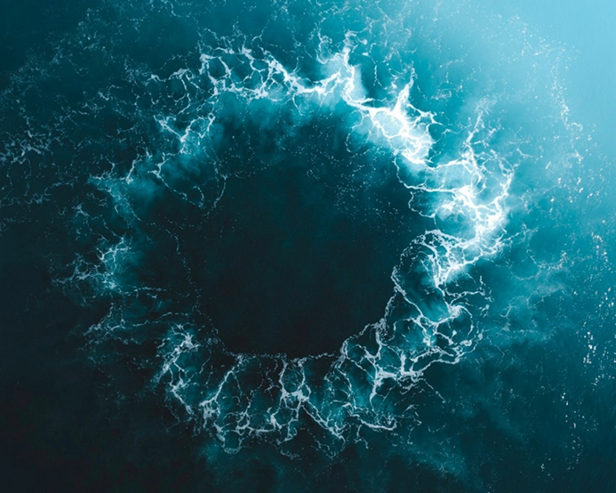

Capacity Building Panel, BBNJ Symposium, Edinburgh, f.l.t.r: Fuad Bateh, Judith Gobin, Julia Schutz Veiga, Harriet Harden Davies, Kwaku Kyeremeh, Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki

The CBTMT panel (Recording, Session 4) offered a way for BBNJ experts from different regions to share their experiences, use concrete examples from their regions, mention different types of CBTMT needed, suited to their situations and in relation to specific package elements of the agreement. Rather than simply pointing to the – overall agreed – need for CBTMT, the symposium offered a space to dive deeper into what is needed for BBNJ implementation, how and by when, concrete examples of how the CBTMT part can support developing States and concrete actions that will change the status quo, highlighting important topics of support and pointing to scenarios and examples that stakeholders at the symposium could relate to. With an audience of negotiators from both developed and developing countries, representatives of non-governmental organisations, the private sector and academia, the panel sought to encourage action for successful implementation with concrete and implementable ideas.

Dr. Harriet Harden-Davies, Director of the Nippon Foundation-University of Edinburgh Ocean Voices Programme gave introductory remarks as the keynote on the importance of CBTMT and what it entails, the CBTMT text, how it moves forward from UNCLOS and what the key achievements are and where there are remaining questions.

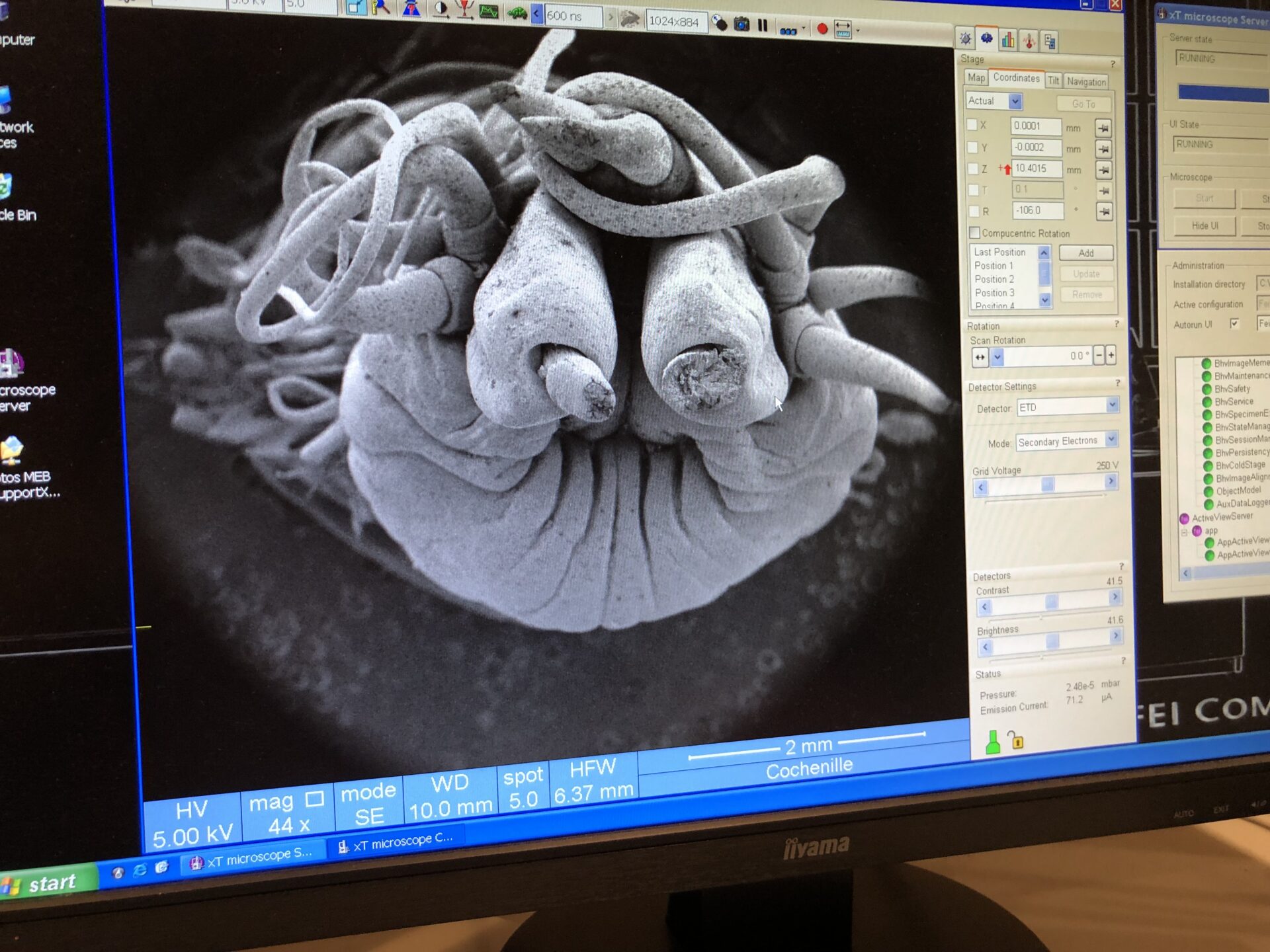

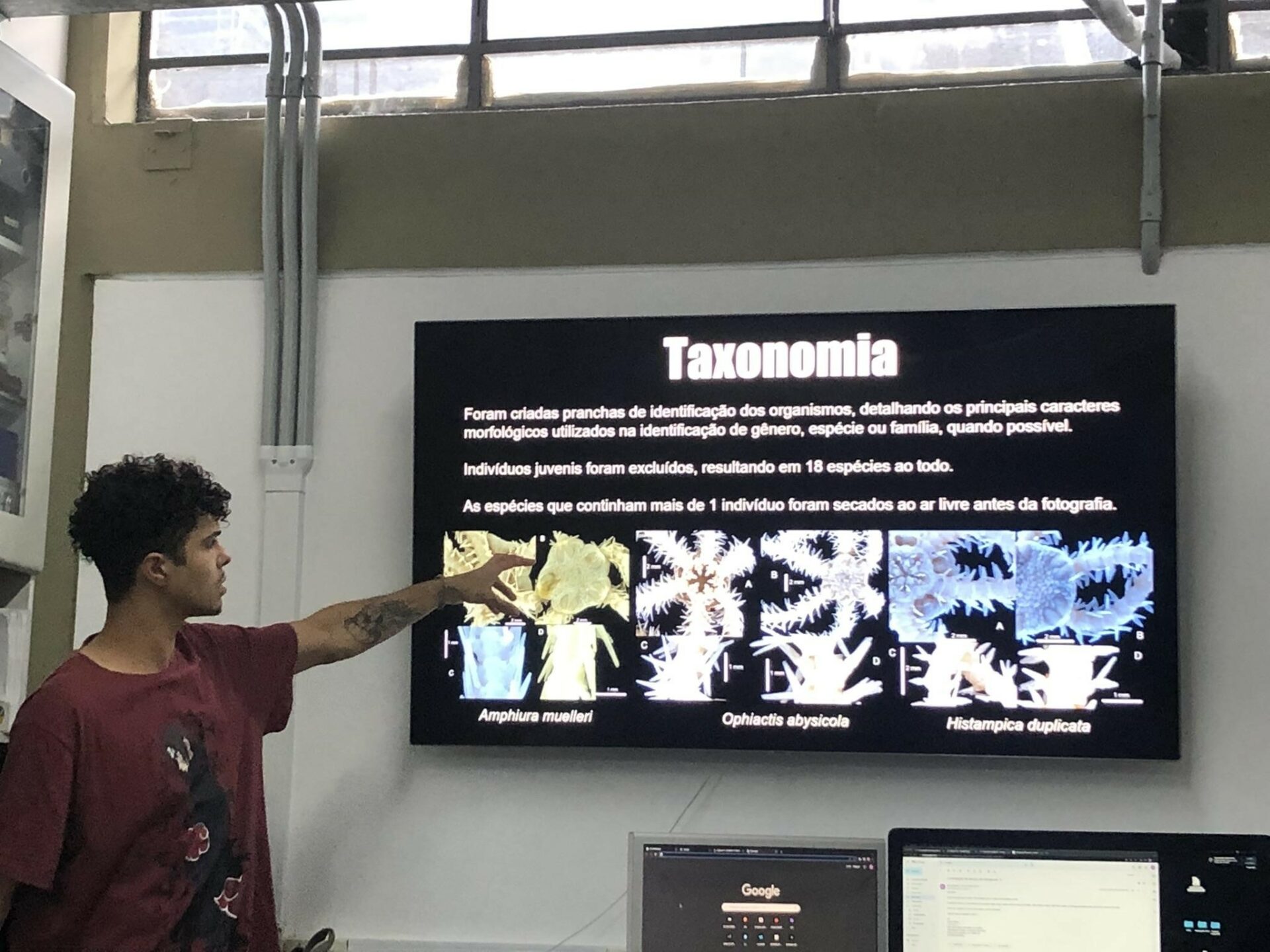

Judith Gobin, Professor at the University of West Indies, elaborated on key needs of small island developing states (SIDS) as regards CBTMT. With an overview of some SIDS institutional and human resource needs, national and local examples served to pin down concrete capacity building types that would be useful when looking at the next steps in trying to support the implementation of the overall agreement.

Kwaku Kyeremeh, Associate Professor of Chemistry, University of Ghana, provided an overview of Research in Africa by using the University of Ghana as an example and pointed to important gaps that could be filled with the BBNJ agreement, such as implementing centres of excellence.

Julia Schutz Veiga, PhD candidate in Law at NOVA School of Law and visiting fellow at the Ocean Voices Programme who was a legal adviser for the Brazilian delegation from 2019-2023 during the BBNJ process addressed unlocking Intellectual property constraints to transfer knowledge and technology and shared her ideas on how to prepare BBNJ implementation prior to entry into force by advancing details of the CBTMT committee.

Fuad Bateh, former IGC delegate and representative of the 2019 G77 & China Chair for BBNJ highlighted the importance of the BBNJ agreement for all States – including land-locked countries. He pointed to challenges of resource mobilisation and proposed a Preparatory Commission for the time before the first COP to formally facilitate early implementation.

The panel overall agreed that CBTMT is not only a crucial pillar of the agreement, it is also interlinked with all other pillars of the instrument and necessary for timely and efficient implementation.

Ensuring equity through CBTMT

There was one topic that was picked up constantly throughout the panels and the symposium discussions: Equity. Attendees of the symposium agreed that for an effective implementation of the BBNJ agreement, several equity concerns must be addressed.

With inclusive language, the BBNJ treaty has recognised voices of developing countries and brought marine scientists to the fore. While many don’t have sufficient human capital, training and finances to implement the BBNJ agreement, scientific training and expertise have advanced significantly over the years and they are ready to support implementation. In this regard, South-South cooperation can be facilitated, with identifying mentors in the region to support other developing States.

Sustained science, however, is a challenge. The aim is to support developing countries’ scientists in the long-term. Regional alliances and private and public partnerships are important. What is needed in the case of SIDS is financing and inclusivity. SIDS scientists need to be included from the start, as currently, a structured overall inclusion is missing. SIDS scientists need to be true collaborators and not simply added to scientific publications. Funding is essential for their scientific trainings to undertake EIAs and identify ABMTs and MPAs.

Similar challenges can be seen in the African region. Capacity building and transfer of marine technology for African universities would be most beneficial by establishing centres of excellence. In this regard, also regional centres could channel expertise and offer improvement for the entire region. The introduction of workshops, programmes, courses and trainings will be valuable.

In relation to the transfer of marine technology, there is a need to recognise the challenge for Global South countries – while having trained scientists – to be part of actually developing technology. Meaningful participation of Global South scientists will include setting up the necessary basis for the development of technology on the global market, rather than simply transferring marine technology that was developed in the Global North.

Ocean health matters to all. Equity demands leaving no one behind – even States that are not islands or coastal are entitled to dedicated capacitation efforts (Harden-Davies et al., 2024). It will be crucial that governance of the global commons will be global and not left to a few countries with the capacities to research or exploitation of ocean resources. Meaningfully engaging in BBNJ governance also means to enable participation and invite diverse ideas. The next generations will be living with the ocean and are entitled to benefit from a harmonic human-nature relationship. In this regard, the involvement of youth is crucial. Ocean literacy efforts by initiatives of the UN Ocean Decade and beyond need to be supported and expanded, which will raise knowledge and awareness. The scientific and technical body that will be set up to inform implementation still needs to be further defined and details to be thought through to ensure equitable participation and representation (Gaebel et al., 2024). Here it is crucial that diverse disciplines and regions are represented. Different forms of knowledge, such as indigenous and local knowledge is to be regarded as equally relevant as scientific knowledge, when informing the implementation of BBNJ (Mulalap et al., 2020). CBTMT is much more than financial donations and includes requirements regarding gender equality and representation.

While ocean health is crucial to current and future generations, as well as non-humans inhabiting the ocean, currently, there is insufficient protection of areas beyond national jurisdiction. With the Global Biodiversity Framework, adopted in December 2022 under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), State parties have set a political signal to commit to meeting the target of 30% protection by 2030. The BBNJ agreement can support the 30×30 target in ABNJ through the establishment of area-based management tools (ABMTs), including marine protected areas (MPAs). While the BBNJ instrument is the governance framework to achieve the GBF target in ABNJ, a clear structure on next steps is needed and would offer a valuable rationale for ratifying BBNJ, as implementation serves GBF commitment, as well as supports Paris Agreement objectives.

To be able to fund implementation, a responsibility of the international community is to find a credible way to fund capacity for e.g. raising the percentage of protected areas in ABNJ from approximately 1.4% (CBD, 2022) to the GBF target of 30%. The Global Environmental Facility (GEF) is identified in the Agreement as one funding resource to cover part of the BBNJ implementation costs, but it is not possible for the GEF to cover even the ABMT part of BBNJ comprehensively. Donors suggest any significant resource mobilisation should be expected only after entry into force of the agreement, yet this under-appreciates developing states officials’ likely concern for where shall the funds be sourced to fulfil legal obligation to effectively implement the BBNJ agreement. Hence, a pledging conference would be a valuable contribution to BBNJ’s implementation: It would encourage confidence and accelerate ratifications by debt-strapped developing countries.

BBNJ Agreement – what now?

With the adoption of the BBNJ agreement the first step is done, however, as it currently stands it is an agreement among nations that still needs to be ratified by another 53 States to enter into force and officially have legally-binding power to only those States that signed and ratified it. 120 days after the 60th ratification, the agreement enters into force and the COP meets within 1 year after. Until entry into force – not to mention the COP meetings and agreement on the details that remain to be negotiated among member States – quite some time can pass. Looking at other agreements and the difference between adoption and entry into force, the BBNJ agreement can be lucky if in force in the next few years.

The BBNJ agreement builds the basis for future governance of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. Yet, several issues regarding CBTMT are still to be resolved, which are not or only broadly defined in the treaty text including (i) country-driven needs assessments and action plans; (ii) measures to monitor and review the quality of capacity building; (iii) support for key people and processes, including in relation to the Committee; (iv) information sharing and cooperation; (v) funding (Harden-Davies et al., 2024). There needs to be an inclusion of Global South countries in the development of technology and its transfer. Intellectual property (IP) rights are the elephant in the room but need to be discussed when challenges in the transfer of marine technology come about. Are there alternative methods to circumvent or facilitate the application of IP rights in the transfer of marine technology developed to solve, improve and/or mitigate impacts related to the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity? The CBTMT committee serves to facilitate access to and transfer of marine technology, which will need to be on the agenda of the COP meetings: The CBTMT Committee stands as a beacon of hope, guiding international cooperation and fostering a future where marine ecosystems thrive despite the pressures of climate change. The BBNJ Agreement introduces a significant advancement in the form of a monitoring and review process (Article 47), and here, the role of the CBTMT Committee shines prominently. This committee is pivotal in evaluating the effectiveness of CBTMT initiatives, employing a range of vital metrics, including indicators and results-based analyses.

Literature highlighting current weaknesses in ocean governance can facilitate the identification of strategies and measures for reports and recommendations to be made by the CBTMT committee. For instance, the Global Ocean Science Report (IOC-UNESCO, 2020) highlights specific areas of concern that the committee can address in the future. These include (i) information regarding patents, particularly those related to green technologies, to facilitate the access to and transfer of marine technology; (ii) information regarding the needs and priorities of developing countries; and (iii) opportunity to fill the scientific and technological gap among states, as outlined in the UNCLOS preamble.

While the Conference of the Parties meetings will be crucial in clarifying the remaining issues, there are several steps that can already be taken prior to entry into force to ensure smooth implementation of the new agreement.

Taking action before the first COP

Already now – before entry into force – we need to make a strategy to get funding for building capacity and training. A draft document of technologies we are hoping to transfer would be valuable. It is crucial that skill gaps are identified and addressed. Workshops and support by relevant institutions offer opportunities to build knowledge and capacity.

There is little awareness of the importance of areas beyond national jurisdiction in SIDS – even though the international seabed authority is based in Jamaica. SIDS scientists need to be trained to serve on committees, which is key to equitable implementation of the BBNJ agreement.

Ratification of developing countries can be encouraged by clearly stating what is needed, how much funding is required to achieve it and where it will come from. There will be a benefit for bringing in new actors in BBNJ and collaborate with the private sector. Other ideas include an early implementation fund to assist countries that are signatories to ratify the treaty. The fund could provide assistance in terms of the legal work (assessment of national laws, institutional structures, stakeholder involvement mechanisms etc.) that may need to happen in the country to make it ready to ratify. More importantly, the fund could also get countries started on the path of determining their priorities for the BBNJ Agreement, and subsequently start assessing what existing capacities and technologies they have, and what they might additionally need to reach their priorities. This could be a sort of a pre-cursor to a full-on needs assessment, and start dialogues around potential modalities for regional implementation collaboration on how regions might be more effective through sharing expertise, technologies and resources. Such an early implementation fund could help provide certainty to countries that the BBNJ Agreement will be implementable by them, similar to the Montreal Protocol’s Multilateral Fund, which provided assistance to countries prior to ratification. In this way, various aspects of the BBNJ Agreement implementation could be supported in a holistic and non-duplicative way, building on previous efforts and institutions.

To identify the needs, it is essential to mobilise funding resources to undertake inventory as soon as possible. Needs assessments can now already be funded to identify how BBNJ can best support different regions and countries. The Global Ocean Forum has prepared a draft ToR for a comprehensive inventory of BBNJ relevant CBTMT which shall further include an initial costing of required CBTMT following from national, regional and global needs assessment.

A consortium of UN agencies and other institutions with Marine CBTMT mandates and expertise could mobilise to contribute, including WMU-GOI, UNESCO-IOC, FAO, UNEP, UNDP, World Bank, IUCN, Global Ocean Forum. This information gap must be addressed to inform subsequent decision-making including deployment of development assistance.

The interim Secretariat is currently planning a Preparatory Commission to prepare States for entry into force and to provide a formal forum to discuss important issues for the first COP and BBNJ actors are coming together from 24-26th June, 2024 for an organisational meeting. What is now needed is the Preparatory Commission to bring in more inclusive voices from civil society and the private sector to support provisional and early implementation among other critical preparatory guidance to the interim secretariat, as well as third parties such as the GEF Secretariat (i.e. directing resource deployment priorities in multi-year GEF programming in advance of BBNJ entry into force). The private sector is the biggest actor in ABNJ. The operative United Nations General Assembly resolution could provide a mandate to the UN Global Compact as the key UN institutional interlocutor with the private sector to mobilise support/engagement on achieving objectives of the BBNJ interrelated with objectives of the CBD GBF and UNFCCC/Paris Agreement.

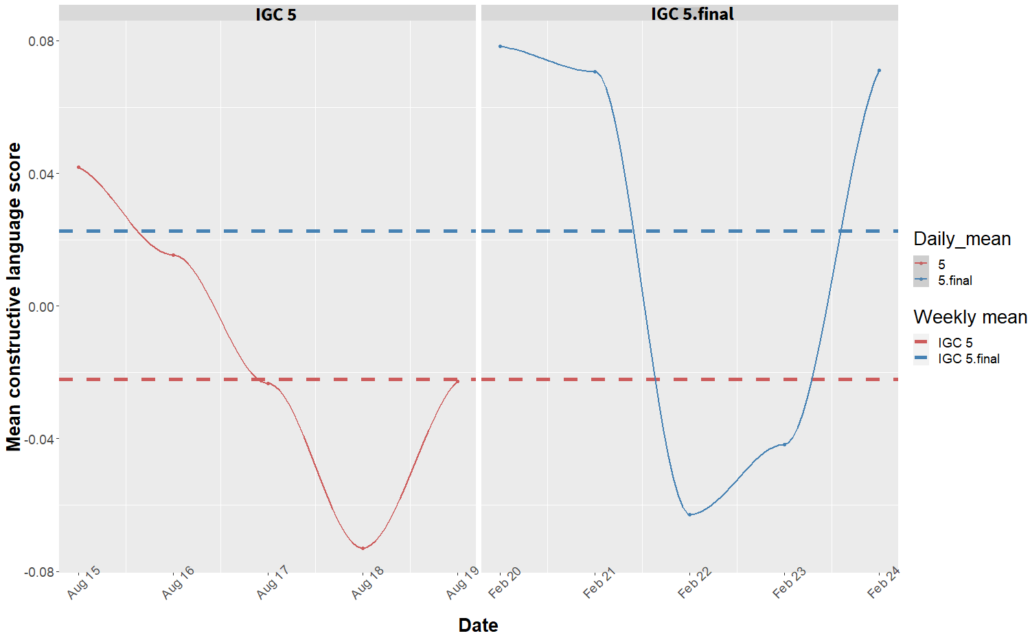

Measuring implementation success

Surely all members of the agreement would like to see effective and timely implementation. However, measuring the implementation success of the capacity building and marine technology transfer chapter of the agreement might not be as straightforward. With different regions requiring different types, forms, activities and cooperation of CBTMT, easy quantification is not given and goals/targets/reference points might not be as clear as for other topics.

In the context of ABMT/MPAs and the BBNJ securing the GBF Target 30×30, progress can be measured by looking at the percentage of MPAs in ABNJ. Another metric is partnerships organised to establish OECM/MPAs and the number of trained experts/specialists/agents of change in support of OECM/ABNJ. Similarly, in the context of EIAs, the metric is the number of trained experts/specialists/agents of change on undertaking EIAs with specific appreciation of ABNJ context.

One way to measure success of CBTMT is to aim at increased participation by the Global South in developing and patenting emerging technologies, decreasing North-South funding, enabling greater independence for the Global South.

Conclusion

The new BBNJ agreement adopted and already signed by 91 countries offers an important milestone towards restoring our relationship with the ocean and life within it. For the first time, processes to establish marine protected areas and conduct environmental impact assessments in areas beyond national jurisdiction are universally regulated, offering a more concrete framework on how to conserve and sustainably use marine biodiversity. The “trendy” agreement, as some BBNJ symposium attendees called it, provides a living document, with responsibilities to continuously and jointly work towards structures to govern the fair and equitable use of marine genetic resources and ensure a timely response to current and upcoming challenges that the health of marine biodiversity is facing. The agreement is, thus, not the solution to marine biodiversity loss and unequal distribution of ocean resources amongst humans, but it offers a common ground, a legally-binding instrument, adopted – by consensus – by the entire international community. A solid ground to build on for future solutions, integration of different scientific disciplines and knowledge forms through a future scientific and technical body to support implementation, increased cooperation and coordination among the other relevant regional, sub-regional and sectoral bodies that are active in areas beyond national jurisdiction under their respective mandates, and many more meetings of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to negotiate further details of the agreement that are yet to be developed. CBTMT acts as an enabler across all other core topics of the BBNJ Agreement and can significantly channel timely and efficient implementation.

References

CBD (2022). CBD/COP/15/9 (30 October 2022). Review of Progress in the Implementation of the Convention and the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2022. Para 14 of Subsection B “Aichi Biodiversity Target 11” Retrieved from: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/53a6/9a0b/dc1cf7bc6eb5c870243ad5a9/cop-15-09-en.pdf

Gaebel, C., Novo, P., Johnson, D. E., & Roberts, J. M. (2024). Institutionalising science and knowledge under the agreement for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ): Stakeholder perspectives on a fit-for-purpose Scientific and Technical Body. Marine Policy, 161, 105998. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105998

Harden-Davies, H., Lopes, V. F., Coelho, L. F., Nelson, G., Veiga, J. S., Talma, S., & Vierros, M. (2024). First to finish, what comes next? Putting Capacity Building and the Transfer of Marine Technology under the BBNJ Agreement into practice. npj Ocean Sustainability, 3(1), 3. doi:10.1038/s44183-023-00039-1

IOC-UNESCO (2020). Global Ocean Science Report 2020–Charting Capacity

for Ocean Sustainability. K. Isensee (ed.), Paris, UNESCO Publishing

Lothian, S. L. (2022). Marine conservation and international law : legal instruments for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Mulalap, C. Y., Frere, T., Huffer, E., Hviding, E., Paul, K., Smith, A., & Vierros, M. K. (2020). Traditional knowledge and the BBNJ instrument. Marine Policy, 122, 104103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104103

UNCLOS (2023). Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction. Retrieved from: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXI-10&chapter=21&clang=_en