Finalizing an Ocean Treaty: Drowning in detail or sailing towards compromise?

By Arne Langlet, Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki, Paul Dunshirn, Silvia Ruiz Rodríguez, Daria Sander and Alice Vadrot

After nearly two decades of negotiating a new legally binding agreement to conserve and sustainably use marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ treaty), Parties to the United Nations hope to finalize the treaty text during IGC-5 in New York. The MARIPOLDATA Team is following the discussions closely. At the halftime of the negotiations, we provide an overview of the issues discussed – and the outstanding elements that are still to be negotiated in the coming week.

The negotiation room; Source: Author

The first week of negotiations was filled with a diverse agenda, going through all issues in the four elements of the package – marine genetic resources (MGRs), area-based management tools including marine protected areas (ABMTs/MPAs), environmental impact assessments (EIAs), capacity building and transfer of marine technology (CBTMT). Whereas the discussion in the first week was largely driven by re-structuring provisions, some important substantive conflicts need to be solved in week two. To finalize an ambitious and future-proof treaty, states should address the institutional set-up of the BBNJ Agreement to create a few but strong and effective institutions that have the capacities and mandate to monitor and review compliance across package items.

MGRs – will restructuring be enough?

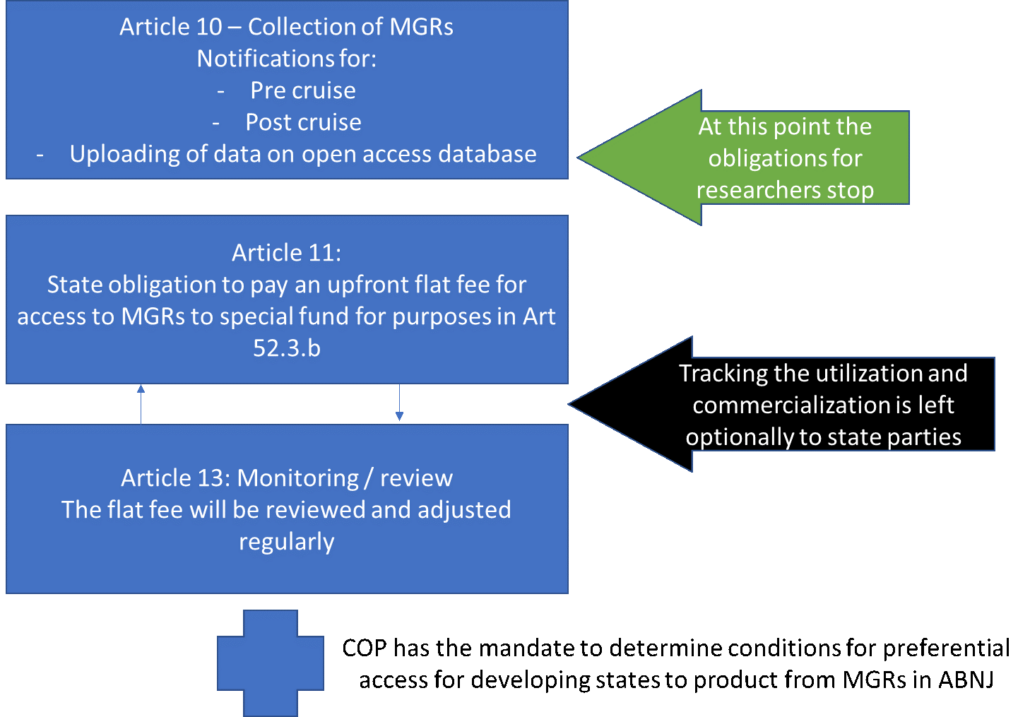

On day one of the fifth Intergovernmental Conference (IGC 5), negotiators dived right into one of the most difficult topics of the BBNJ negotiations: MGRs, including questions on the sharing of benefits. Articles 10, 11, 11bis and 13 of the draft text were addressed during the first week. Negotiators approached commonly acceptable solutions by streamlining and rearranging elements of the above-mentioned articles with regards to the modalities for notification of cruises and benefit-sharing. It is by now accepted by all delegations to have pre and post cruise notifications, as well as a notification to the clearing-house mechanism (CHM) when the relevant data has been uploaded to an open access database. By looking at notifications and benefit sharing separately, common ground could be found regarding the chronology of notifications. In regards to benefit-sharing, the many and intense informal informal sessions on MGRs largely reproduced the conflicts that observers know from previous IGCs on whether to include mandatory monetary benefit-sharing and how closely MGR utilization should be monitored. By the end of week one large part of the chapter had become re-structured and acceptable to most, leaving the big issue of the types of benefit sharing to week two. Although some delegations that previously had strictly rejected any sort of monetary benefit sharing indicated to consider this as long as it would be decoupled from tracking utilization and commercialization.

This work in re-structuring and the new flexibility in positions opened many discussions on monetary benefit sharing in the corridors. The idea that monetary benefit sharing can become a reality in the form of a de-coupled/flat rate/flat fee/upfront payment gained traction among delegations from many different alliances. This approach was recently developed by the ‘DSI scientific network’ for similar discussions in the context of the Convention of Biological Diversity and appeals to very opposing interests. It would require developed countries to pay a flat fee/upfront payment on a regular basis, which would in turn allow scientists/universities and companies to freely access and utilize MGRs without having to notify each step of the MGR development/research to the CHM. This has benefits for 1) developing countries, which would be able to receive guaranteed monetary benefit for capacity building from day one of the entry into force of the treaty and for 2) developed countries, which would be able to guarantee their researchers and companies the free engagement with MGR research. The amount of benefit sharing developing countries receive could be weighted by how much genetic sequence data they contribute to openly accessible databases, creating incentives to fill existing biodiversity knowledge gaps in their own regions.

Sketch of potential MGR part containing monetary benefit-sharing from a decoupled flat fee. Source: Author

ABMTs/MPAs

Throughout week one of the IGC5, negotiations about ABMTs/MPAs have been slowly advancing on a few issues. Parties agreed on including a separate article on objectives into this part on ABMTs/MPAs, however, there was a desire to further streamline the text and details will need to be negotiated in the coming discussions. Broad agreement, even though no consensus, was found on the need for an inclusive consultation process and value for time frames for consultations to avoid delays in the establishment of ABMTs/MPAs. Discussions later in the week included the idea to add a provision to respond to emergencies with temporary measures into the ABMTs/MPA part. Key issues, however, about the purpose of such tools and the responsible body for establishing them, were postponed to the second week.

What is the purpose of ABMTs/MPAs?

Last week discussions about the definitions of ABMTs and MPAs continued, including whether such definitions are required to be set in the treaty. While some states want to differentiate between conservation and sustainable use objectives, others prefer not to draw such a clear line, or even avoid a definition altogether. While discussions still continue, the direction seems to steer towards a slight difference between the definition of ABMTs: 1) to have conservation and sustainable use objectives- and of MPAs 2) to have the primary objective of conservation but still allow sustainable use elements.

Another relevant discussion was postponed for the second week: The relationship between the future BBNJ Agreement and already existing regional and sectoral frameworks and bodies. Existing bodies and frameworks have shown to be insufficient for a holistic marine biodiversity governance in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) (Gjerde, 2019). While the mandate of the BBNJ agreement would close these gaps of fragmented ocean governance and provide the global and holistic answer to biodiversity loss, it does need to recognize and fit into the existing biodiversity regime complex. In this regard, discussions from previous IGCs on the effective interplay and definition of complementarity continued, as well as fears that the BBNJ Agreement would introduce a hierarchy among existing frameworks and bodies and undermine their mandates. Large fishing states preferred to leave the establishment of ABMTs/MPAs to existing bodies that manage activities in ABNJ, such as Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). It was suggested in case of issues that fall outside of their mandate to get together and discuss the establishment of separate new bodies to take on these tasks. A large number of states disagreed with this suggestion by emphasizing the need for the BBNJ agreement to take a holistic approach to marine biodiversity governance in order to close these gaps.

The following days need to give time for discussions on how the BBNJ agreement will not undermine the work of existing bodies and frameworks, while still fulfilling its own mandate: the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in ABNJ. As the Swiss delegate reminded everyone in the room that “the high seas negotiators seem to act as there is us and then the ifbs [relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies]. Those are the same countries […] They are different instruments but in the end there are the same countries.”

Going into the second week it is now important to call into minds the necessity to differentiate between ABMTs and MPAs in order to ensure sustainable use through various different tools (ABMTs), while enabling marine conservation (MPAs) (Johnson et al., 2018). In light of the obligation under UNCLOS to protect and preserve the marine environment, it is urgent to acknowledge the need to use marine resources sustainably in the global ocean and allow for certain areas to be conserved that require protection. While a number of States emphasize their rights (freedom of the high seas) for ocean use, it is important to also consider obiligations (to protect and preserve the marine ebnvironment), particulalry when considering the current unequal proportion of human use and conservation of the high seas (https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/03/a-path-to-creating-the-first-generation-of-high-seas-protected-areas).

Another key question will be how States agree on the responsible body to implement ABMTs, including MPAs and how the new BBNJ agreement could fit into the existing ocean governance cooperatively while ensuring increased conservation and sustainable use measures. In these discussions, the possibility of “opt-out” provisions were preferred by a few States with the argument to achieve a higher participation of Parties, which would, however, also lead to a lower level of ambition and could enable States to commit to conservation and sustainable use only when convenient for them. The second week of negotiations will show whether States can agree on common definitions of these measures and their purpose to achieve the objective of the overall treaty: conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity.

Assessing human impacts on the High Seas

Discussions about the EIAs part advanced at the end of the first week. Many proposals, including cross-regional, were introduced by a number of States and flexibility was shown to discuss and include them. There is a general agreement that firstly, Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs) are valuable and secondly, cumulative impacts need to be taken into account. The question on whether or not SEAs should be mandatory or voluntary is still up for debate. Further discussions surrounded the types of impacts that are supposed to be addressed and the question to include or exclude other impacts besides environmental ones.One key question remains: – but this discussion was probably intentionally avoided by the facilitator until the second week – whether the agreement should look at a location-based or effects-based approach. This question has divided the international community since the beginning of the BBNJ negotiations but is a major point of interpretation: is the purpose of the BBNJ agreement the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in ABNJ or is it the establishment of measures to regulate activities in ABNJ for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in ABNJ? One approach would look only at what happens in the high seas and regulate accordingly. The other is more holistic and would include the regulation of activities with IMPACTS on marine biodiversity, regardless of where these activities take place. There is currently no consensus on this point. The EU has introduced a proposed text that would enable states to undertake EIAs of activities with potential harmful effects on ABNJ but which are undertaken in areas within national jurisdiction with the voluntary option to do so.

Another point of discussion that is highly contested is the question of the possibility of BBNJ setting global standards or guidelines/guidance. Some States show reluctance to mandatory global standards for EIAs and emphasize the responsibility of States proposing new activities to conduct their own EIAs (up to their own standards which might be high or low depending on the national contexts). Further, those States have a strong preference to not only conduct the EIA themselves, but also to evaluate them and decide whether or not their proposed activities can take place on the high seas. This point of decision-making is the most contested, as a number of States and regional groups oppose the idea of a purely state-led procedure of EIAs. In their view, there would need to be some sort of global check for harmful activities that will be undertaken in areas beyond national jurisdiction. There has been a compromise option on the table, introduced by CARICOM and PSIDIS at the end of IGC3 that is debated in current discussions. The idea is to have a mixture of state-led and international oversight to accommodate both sides.

Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki and Arne Langlet in front of the UN building in New York City where the negotiations take place. Source: Author

CBTMT – what is the right amount of detail?

In the chapter on capacity building and transfer of marine technology (CBTMT), the disagreements about the strength of language that characterized IGC 4 continued during the first week of IGC 5. The “usual” difference between the preferences of 1) developed countries to formulate “shall promote” and 2) developing countries to have “shall ensure” for stronger and more certain language in Art 44.1. has not been overcome so far.

Moreover, developing countries generally prefer the inclusion of detailed language and developed countries prefer to leave details out and potentially move this to the upcoming (Conference of the Parties (COP(s)). Ironically, both sides claim that their approach would future-proof this instrument.

This difference could also be observed in discussions about whether to include a detailed list of types of CBTMT in Art 46 and/or the annex. Whereas the fear that a lack of detail means a lack of implementation is understandable, the fact that updating a list that is treaty language (in annex or main body) would require some countries to always re-ratify the treaty when the language changes:a detailed list that should be updated cannot be the solution. The answer may lie in mandating the relevant BBNJ institution(s) to establish and update a list.

While all states agree that CBTMT efforts shall regularly be monitored and reviewed, it remains unclear who/which body should undertake this. Should it be carried out by the COP, a working group or a committee? In general, developed countries prefer to mandate the COP to monitor and review CBTMT, whereas developing countries prefer to establish an extra committee for such purpose. This discussion can be placed in two different broader visions on this treaty: while many developed states prefer a “slim” version of the BBNJ agreement with only a few bodies, developing countries prefer to establish a number of bodies that would monitor and review implementation of CBTMT, update a list of types of CBTMT and monitor benefit sharing of MGRs.

In any case, it seems to be agreeable to all states that the COP shall be the decision-making instance. Aggregating the monitoring and review powers in one body, the discussions on whether to establish a new body does not have to be repeated in each meeting about the individual package elements but can maybe be driven forward for the treaty as a whole. Although there are different package elements, it is one common treaty and monitoring and review of implementation should be done on an equal footing for the treaty as a whole.

Crosscutting Issues

Secretariat

Under the crosscutting chapters, the negotiators addressed crucial provisions for the effective implementation of the BBNJ agreement. Among these were questions on the secretariat. UNDOALOS had distributed an estimate of the personnel and resources needed if UNDOALOS were to be mandated with the BBNJ secretariat. Many delegates expressed their concern that the estimate for the required financial and human resources may have been too conservative to fully address the complete spectrum of activities that the secretariat is to administer. Representatives of UNDOALOS were in the room to openly answer questions on the practicalities of making UNDOALOS the BBNJ Treaty secretariat. One important issue was raised concerning the budget of the future secretariat. States discussed that, as UNDOALOS is financed through the UN regular budget, it could be difficult to ringfence extra budget for BBNJ tasks and all UN member states, whether BBNJ party or not, would be involved in negotiations over UNDOALOS’ budget. This means that on the one hand, non-parties to BBNJ could exert influence over the finances for a treaty they are not part of and on the other, that non-parties would have to contribute financially to the secretariat of a treaty they are not part of. This needs to be considered even though many strong arguments for making UNDOALOS the Treaty’s secretariat were highlighted such as: its location in the UN headquarters in New York, its established working relations with other bodies and most importantly its large experience in dealing with ocean matters.

Funding

According to State’s requests during previous IGCs, a representative from the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) was present in the room during negotiations over the funding chapter. The representative was able to contribute to practical questions on the funds that shall be used to finance activities under the BBNJ Treaty. On the one hand, developing countries urged the need to specify between institutional and non-institutional funding and required the establishment of a special fund under Art 52.3b that is to be used for financing capacity building activities. On the other hand, developed countries warned against a potential doubling of funds. It was also warned that being too prescriptive may prevent the GEF financing BBNJ activities because it could not become subordinate to the BBNJ instrument. However, the GEF representative was able to alleviate these concerns as it was made clear that the GEF could work under strict guidance and authority by the COP and also next to other existing funds.

Scientific and technical body

Under article 49.2 of the draft text, states discussed the composition of the scientific and technical body. Negotiators aimed to find the most precise and inclusive terms to create a scientific and technical body that represents all appropriate expertise and regions of the world. Proposals were made to delete the word “scientific” or add the term “technical” and/or “suitable” in relation to qualifications necessary for the scientific and technical body. The role of the STB was discussed in more detail in the parts of ABMTs/MPAs and EIAs for advice and decision-making. Overall agreement was seen on the advisory function of the STB in both sections, but leaving details open as regards to the extent to which the future body will be involved in the identification of ABMTs/MPAs, the process for EIAs, setting standards/guidelines and review of reports.

COP

Finally, the procedures and decision-making rules of the COP are part of the most important issues for an effective implementation of the BBNJ agreement . In the past, this topic divided States into those that wanted exclusively consensus-based decision-making and those that argued for a majority-based system when consensus could be reached. Although a few states still insist that all decisions must be made by consensus, most states have by now accepted that the instrument needs to be able to find a way forward when consensus cannot be reached. While all states clearly strive for consensus decision-making, lessons from other international institutions have shown that if only consensus decision-making is possible, individual states can easily block the implementation of COP decisions. Another important decision must be made in regards to the interim procedures while the BBNJ institutions are not set up yet and the COP has not met. Agreement largely emerged to use the rules of procedure of the UN General Assembly until the COP has decided on its own rules of procedure and to use UNDOALOS until a dedicated BBNJ secretariat has been established (or UNDOALOS remains secretariat). Hence, agreement on some important steps preparing for successful implementation seem tangible within a short time.

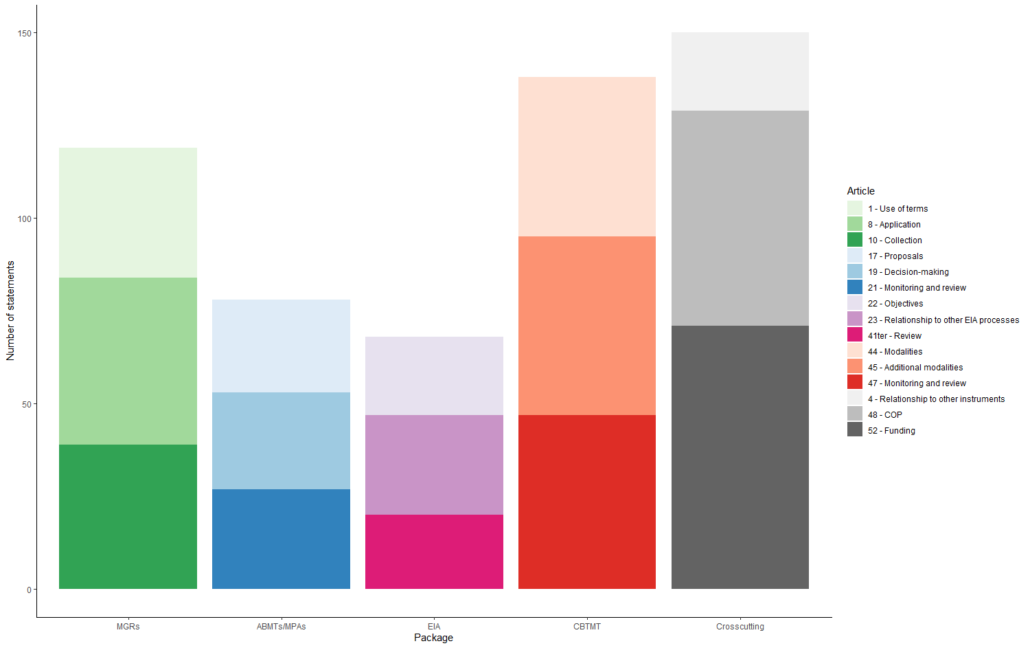

Graph – most discussed articles per package item:

The graph shows the three articles in which states made the most statements per package item. We see that articles that are in direct relation to future BBNJ institutions tended to be the most discussed in each package item. This includes: COP and Funding (crosscutting); Monitoring and review (CBTMT); Relationships to other EIA processes and Review (EIA); Decision-making and Monitoring and review (ABMTs/MPAs) and Collection of MGRs. Therefore, we highlight the importance to clarify the institutional structure and competences for a successful finalization of the Treaty and welcome the plan by President Rena Lee to host a special session on institutional issues later this week. (please note that in the EIA Chapter, negotiators tended to address many articles in one statement which decreased the overall number of interventions).

Conclusion – equipping the BBNJ with strong and flexible institutions:

At this stage of the negotiation process, states and their representatives have to make some consequential decisions on what to focus on during the remaining 5 days. In all of the 5 package elements, some important steps towards compromise were taken: the potential for monetary benefit sharing in MGRs; agreement on the overall process for establishing ABMTs/MPAs; the inclusion of strategic environmental assessments; the need to regularly review CBTMT efforts; and majority based decision-making possibilities in the COP. However, in all of the package elements some key issues also remain unresolved – in many cases regarding the powers of the future bodies of the instrument. In general, the establishment and composition of bodies under the BBNJ agreement touches upon all the individual provisions in the substantive parts and is arguably one of the deciding factors to whether the agreement will be able to improve the situation in our ocean. Many different bodies have been proposed at some point (COP, secretariat, scientific and technical body, clearing-house mechanism, access and benefit sharing mechanism, CBTMT committee, implementation/compliance committee, special fund) and some states warn against a proliferation of bodies under the new agreement. Indeed, the establishment of up to 8 specialized BBNJ bodies may seem exaggerated. A way forward here could be to tackle these discussions perhaps more broadly, independently of the package element, and perhaps to establish an overall monitoring and review body (as the proposed compliance committee) which works across all package items. Another option could be to give the scientific and technical body or clearing-house mechanism extensive powers to monitor and review elements of treaty implementation on their own initiative. In any case, this means equipping the body at hand with substantial (financial and human) resources and powers to independently and on its own initiative monitor and review the implementation across topics. If the Treaty is to be finished by the end of next week, negotiators may find it useful to rationalize resources to negotiate fewer but stronger bodies instead of getting stuck in the details of substantive provisions. In the end, the ability of the BBNJ bodies to make decisions, monitor implementation and act when needed will make the treaty not only ambitious but also future-proof – and, maybe most importantly, help finalize the treaty.

A good start into the second week was that the secretariat very punctually presented a revised draft text by Sunday afternoon so that negotiations could start from a fresh base on Monday morning.