Assessing the human’s footprint on Ocean Biodiversity

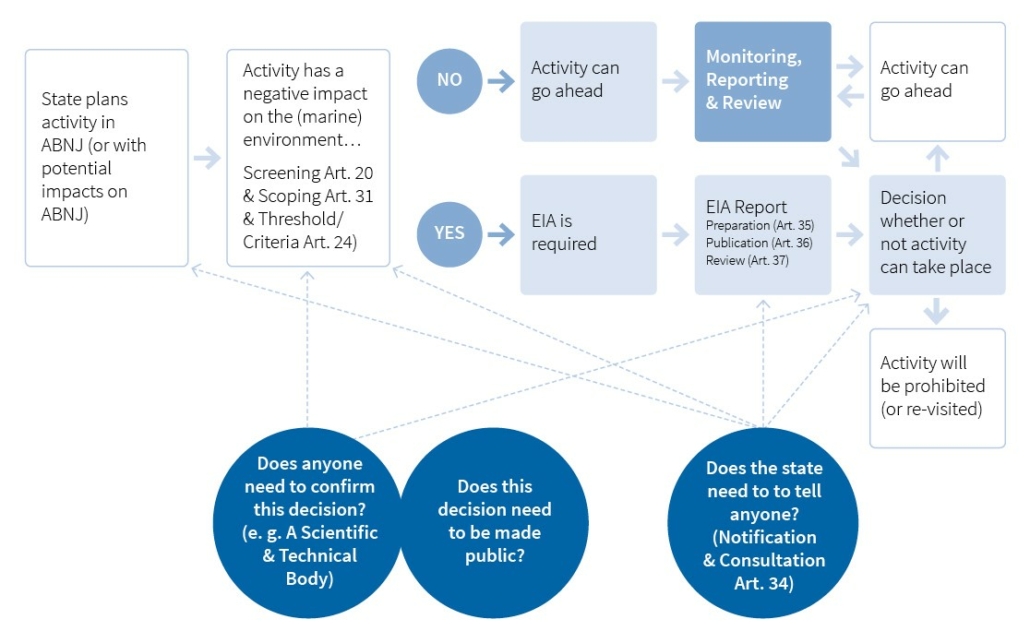

This contribution is part of a MARIPOLDATA blog series on current developments and discussions about the negotiations towards an international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). In this series, the team publishes updates on the four package items under the BBNJ Agreement: Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), Area Based Management Tools (ABMTs) including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and Capacity Building and Technology Transfer (CB&TT). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the planned-to-be final intergovernmental conference (IGC) was again postponed and is now planned for 2022. In the meantime, informal exchanges among state and non-state actors are taking place. The MARIPOLDATA blog series include developments from the online Intersessional Work organized by the UN Secretariat since September 2020, the virtual High Seas Treaty Dialogues, taking place under Chatham House rules, organized by 3 states and a number of NGOs, and the MARIPOLDATA Ocean Seminar Series in which scholars and practitioners present and discuss current issues of ocean governance.

A New Agreement to Conserve and Sustainably Use Marine Biodiversity

Currently, states are negotiating a new legally binding agreement at the United Nations with the aim to conserve and sustainably use marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). The new legal document seeks to fill regulatory gaps concerning the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction in the overarching ocean governance framework (the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)).

Negotiations at the UN level offer an opportunity to regulate so-called “global commons”- resources that cannot be owned by one state alone, but rather have to be shared amongst all for the greater good (Kok, 2011). Global commons include the atmosphere, outer space, Antarctica and the ocean – areas that need to be protected and regulated through international negotiations. In this regard, it is important to consider that decisions about the governance of these areas do not only concern the current human population, but also future generations and other living beings that depend on these areas. With this in mind, there is a huge responsibility that rests on the negotiators and the organizing Secretariat (The United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, UNDOALOS) of finalising an ambitious agreement in due time.

Assessing human impacts on Ocean Biodiversity

One pillar of the new agreement is to establish a process for conducting environmental impact assessments (EIAs) to ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) (Tessnow-von Wysocki & Vadrot, 2020).

Environmental impact assessments evaluate, mitigate and monitor the impact of proposed and ongoing activities on the (marine) environment. In this way, environmental impact assessments serve to predict, reduce and prevent the adverse impacts of human activities (Durussel et al., 2017). Scientists have pointed out shortcomings of the current governance framework (Doelle & Sander, 2020; Durussel et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2016; Warner, 2018). A global, standardized procedure for EIAs is therefore needed, permitting or prohibiting activities in ABNJ, to effectively prevent negative impacts on the marine environment and protect the global commons. Large scale activities are envisaged or already planned that might have an adverse impact on the environment, such as building cities in the ocean – not to speak of the activities in the far future, that we cannot even imagine with our highest technology today.

There are already broad international guidelines in place regarding environmental impact assessments. The United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, is regarded as “the Constitution of the Ocean”[1]. UNCLOS Art. 192 establishes the “general obligation for states to protect and preserve the marine environment”. To reduce and prevent environmental damage by human activities, UNCLOS already sets a broad framework for monitoring and environmental assessment (Part XII, Section 4).

There are already broad international guidelines in place regarding environmental impact assessments. The United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, is regarded as “the Constitution of the Ocean”[1]. UNCLOS Art. 192 establishes the “general obligation for states to protect and preserve the marine environment”. To reduce and prevent environmental damage by human activities, UNCLOS already sets a broad framework for monitoring and environmental assessment (Part XII, Section 4).

UNCLOS Art. 204 requires that States evaluate the risks or effects of pollution of the marine environment and keep under surveillance the effects of any activities which they permit or in which they engage in. Art. 205 further specifies that reports need to be published at appropriate intervals and made available to all States. Art. 206 emphasizes the obligation for states to assess adverse impacts of their planned activities.

The Process of Environmental Impact Assessments under the new BBNJ Agreement

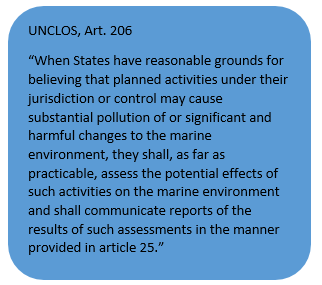

In order to implement the provisions of UNCLOS, the new BBNJ agreement seeks to set out the EIA process in more detail. Throughout the ongoing BBNJ negotiations, a draft text[2] has been developed which is a working document that will ultimately be decided on to become the legal text for the BBNJ Agreement. The section on EIAs is the longest in the draft text and covers the envisaged procedure for EIAs in ABNJ once the treaty enters into force. While an overall procedure is agreed on, important details lack consensus that will ultimately determine the ambition and effectiveness of assessing the impacts of human activities on marine biodiversity in the future. In the following, crucial issues of divergence are described in each of the steps of the EIA process:

EIA process envisaged in BBNJ, Source: Author

- Assessment of what?

The first step of the EIA process is the “Screening” (Art.30) on which basis, it will be determined if an EIA needs to be conducted. There is agreement that the respective state will undertake the screening for activities taking place under its national jurisdiction or control. It is clear that EIAs assess negative impacts on the environment. However, policy-makers have not yet agreed on where to draw the line between impacts that are acceptable – in which case activities can go ahead without the need for an EIA – and the impacts that are potentially harmful so that the planned activity needs to undergo an EIA. As the current draft text stands, there are several options for thresholds when an EIA should be undertaken (Art. 24): The first option is that activities that “may cause substantial pollution of or significant and harmful changes to the marine environment” need to undergo an EIA. The second option that the policy-makers are discussing is much more ambitious, as it calls for an EIA to be undertaken already when the activities “are likely to have more than a minor or transitory effect on the marine environment”[3]. The latter is supported by the regional groups of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS), the African Group and a number of NGOs (Intersessional Work, 2020, own observation; High Seas Alliance, 2020). A point of divergence is also whether the approval of the Scientific and Technical Body must be obtained and whether information should be provided in case the state concludes that an EIA will not be necessary (Art.30 (3)). Also, still under discussion is whether screening of activities will consider the characteristics of the area where the planned activity is taking place or where its effects will be felt. This is particularly relevant regarding the connectivity between the high seas and coastal waters (Livingstone & Jose, 2021) and whether the assessments should be exclusively dealing with impacts that arise from activities that take place in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction– or also considers impacts of any activities (including those within national jurisdiction) that have an impact on ABNJ. The regional groups African group, and PSIDS, for instance, are strong supporters of the latter option (Intersessional Work, own observations, 2020). Possibly, an EIA will be required for areas of significance or vulnerability, even if impacts are expected to be minimal (Art. 30 (2)).

Also under discussion is the scope of EIAs- namely what kind of impacts are supposed to be assessed (Art. 31). The question here would be if there are other impacts, apart from environmental impacts, that would need to be considered, such as social, economic or cultural ones, which is already EIA best practice (CBD, 2010). Scientific literature emphasizes the need to account for cumulative impacts and climate change in EIAs and Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs) (Gjerde et al., 2016; Marciniak, 2017; Sander, 2016)). More recent literature also calls for additional regional environmental assessments (REAs) and the need for the new EIA regime to set out a comprehensive approach of REAs, SEAs and EIAs (Doelle & Sander, 2020). Despite the calls from the scientific community, the question on how to take into account cumulative impacts for environmental impact assessments is still under discussion in the ongoing negotiations (Art. 21bis). Negotiators have until the last round of discussions not agreed on the question how to operationalise Strategic Environmental Assessments (Art. 21bis; Art. 28), and whether or not to include a list of activities that would be exempted from or require an EIA (Art. 29).

- How to assess and evaluate impacts?

One part of the draft text considers who would undertake the assessments and on which basis (scientific knowledge, other forms of knowledge, e.g. traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples and local communities). In this regard, differing capacities of states to undertake EIAs need to be considered and adequate expert advice be guaranteed (Art. 32). It remains to be seen to what extent science advice can be guaranteed through the BBNJ agreement – such as in the form of a pool of experts under the Scientific and Technical Body (Art. 32 (4)). Assessment could also regard prevention, mitigation and management of adverse effects, considering the development of alternative activities to the ones previously planned (Art. 33).

- Who should be kept in the loop?

When activities are planned in ABNJ, the question arises of who should be notified of these plans and included in the EIA process. There are discussions about the inclusion of potentially affected states, relevant bodies, NGOs, and other stakeholders, such as indigenous peoples and local communities, academia and the general public (Art.34). The inclusion of stakeholders, other than the states, that are planning the activity is crucially important for the transparency and legitimacy of the process. However, there is no consensus yet on how participation and consultation of other stakeholders should look like.

- EIA Reports: How to prepare, where to publish?

While there is general agreement that states would be the ones preparing EIA reports (Art. 35) and ensuring that they are published (Art. 36), discussions are still evolving around their contents (Art. 35) and means of publication (Art. 36). Ideas include publishing EIA reports through the BBNJ “Clearing House Mechanism”, a data-sharing platform, which will be established through the BBNJ agreement, but whose characteristics are still undecided. Making EIA reports public – for the Secretariat, the Scientific and Technical Body, other states, intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), NGOs and civil society at large – is important to ensure transparency. A review of the reports by e.g. the Scientific and Technical Body will be necessary for legitimate decisions on whether the proposed activities can go ahead.

- How to decide on the approval of an activity?

The draft text of the future agreement lays out the possibility to establish a review of the EIA reports (Art. 37). Similar to the imbalance in capacities to conduct EIAs, not all states have the same capacity to review EIA reports. Review by the Scientific and Technical Body is currently under discussion within the negotiations. After the preparation of EIA reports, the decision whether or not to allow the proposed activity needs to be taken. In this particular question, views are not aligned and contrasting options are on the table, ranging from unilateral decisions (the state who proposed the activity) to global decisions (the Conference of the Parties (COP)) and a potential role of the Scientific and Technical Body (Art. 38).

- How to check on impacts of authorized activities?

Final considerations in the EIA process regard the monitoring (Art. 39), reporting (Art. 40) and review (Art. 41) of the impacts of authorized activities. Monitoring of authorized activities refers to continuous checks whether the activities that have been authorized do not exceed the threshold of impacts on the environment. While the value of such monitoring, as well as reporting on these findings and their review has been recognized, details are also yet to be decided on.

Key Considerations for BBNJ

There are a number of overarching issues that are not agreed yet but are of paramount importance as they will decide on the future of EIAs for the ocean and its ecosystems.

Relationship to other bodies

The ocean is currently regulated through a fragmentation of different instruments, frameworks and bodies on sectoral, global, regional and subregional levels that cannot comprehensively ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity (Tessnow-von Wysocki & Vadrot, 2020). The relationship between the EIA process established under BBNJ with existing EIA processes under other relevant legal Instruments and Frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral Bodies (IFBs), is not resolved yet (Art. 23). When it comes to conserving and sustainably using marine biodiversity, splitting the governance of the ocean into different regimes for the seafloor and the water column above it, assigns governance capacity over the ocean to different organisations but does not make sense from an ecological perspective (O’Leary & Roberts, 2018). There are separate entities governing activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction regarding the seafloor (i.e. the International Seabed Authority (ISA)) and the water column (several IFBs). The new BBNJ agreement will be responsible for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction and thus provides an opportunity to comprehensively align the efforts by other IFBs.

There is the argument, that BBNJ cannot “undermine” other bodies and frameworks, which can be interpreted differently (Ardron et al., 2014; O’Leary and Roberts, 2017; Quirk and Harden-Davies, 2017; Scanlon, 2018; Friedman, 2019). It is important to note, however, that if a comprehensive framework is the aim, then a coordinated way of governing the conservation and sustainable use needs to be found – in conjunction with the already existing instruments, frameworks and bodies. In this way, mandates will not be undermined, but rather complemented. An idea in this regard is the proposition of joint environmental impact assessments (REAs and data sharing) with potentially affected coastal states, flag states, as well as existing IFBs with decision-making responsibility in ABNJ, including regionally with Regional Fisheries Management Organisations and Regional Seas organisations, and different sectors, with, for example, the International Maritime Organisation (Doelle & Sander, 2020) or the ISA.

There is a large part of the ocean where not all issues are covered under the respective mandates of existing bodies. Therefore, some actors stress the importance for the EIA section being broad enough to consider fish and fishing, as it would otherwise mean that for areas or species that are not covered under existing instruments, frameworks and bodies, there would be no responsible governing entity (Crespo et al., 2019).

Who will govern human impacts on the ocean in the years, decades and centuries to come..?

The main question about EIAs in international waters comes down to who can ultimately take the decision whether or not activities can take place in the global commons. Participation and inclusion of stakeholders in all steps of the EIA process are therefore critical. As mentioned above, in each of the steps, there is a divergence of views of the BBNJ policy-makers who should be notified about proposed activities and final reports and decisions, who should be actively included in the assessment process (assessing, evaluating, reviewing reports), and who should ultimately have the final say whether or not the proposed activity can take place in ABNJ.

While there is agreement that a “Scientific and Technical Body” needs to be established under the BBNJ agreement, the role of such a body for the EIA process is not clear, even though assessing ecological impacts is an inherently scientific question. Theoretically, there would be the possibility to task a global body of stakeholders or the Scientific and Technical Body with a) identifying whether or not an assessment is necessary; b) conducting the assessments; c) reviewing assessment reports and d) deciding whether or not an activity can take place. As elaborated earlier, the negotiations have put a preference on states deciding whether or not EIAs should take place (Screening & Scoping), undertaking the assessments, and taking (unilaterally or multilaterally) the decision whether or not to allow the activity. The discussions include the options for a) the state who is proposing the activity, and b) the Conference of the Parties (COP) – all states collectively – to make the ultimate decision over whether or not the activity can take place. To what extent the Scientific and Technical Body will be able to support countries with a lack of scientific means to conduct EIAs, and to review assessments before decision-making, remains to be seen. Other impacts that might need to be assessed, including social and cultural ones, would additionally require the inclusion of other stakeholders in the process and ideally in all stages of the EIA process.

It needs to be remembered that the ocean is a global common. Areas beyond national jurisdiction is a shared space, and by definition not under the jurisdiction of states. It is rather a space that is home to prestigious marine ecosystems and inevitable for the health of the blue planet. Safeguarding this space is crucial in order to ensure current and future generations’ access to the ocean’s services that we take for granted today. But beyond that, humanity has a responsibility to protect the ocean for its own right and intrinsic value. Some questions should therefore be reflected on during the negotiations for the creation of a new framework that will govern human activities in this shared space that is inevitable for nature and human well-being: Can it be the right of a state to take a decision over activities in areas that belong to everyone and no-one at the same time? Or do we have a collective responsibility as humanity to make sure that our activities do not harm the marine environment and threaten future generations, living beings and their habitats on the planet? Posing these questions can only improve the course of action as we go through this very important process of setting the rules for future use and protection of the ocean.

The international community should be taking joint decisions on how we as humans use and protect this space. While a few governments demand unilateral decision-making over the global commons, a number of state governments have spoken up for a more global approach in the EIA process. Through “internationalizing” the EIA process, it is hoped by some actors that transparency, fairness, accountability and the collective governance of global commons can be achieved. Internationalization can be defined differently by different actors, including the notification of proposed activities and publication of assessment reports and decisions to all interested stakeholders; participation and inclusion of these stakeholders in the process; collective review; up to joint decision-making. Quite some actors would prefer an internationalized process, with the inclusion of a range of stakeholders in the participation and consultation (including indigenous peoples and local communities, particularly relevant in the Arctic region (Doelle & Sander 2020)), a larger role of the Scientific and Technical Body in the review of reports and global decision-making by the COP whether or not activities can take place.

Timely and public access to information on assessments and how decisions were made can ensure transparency and accountability (Doelle & Sander 2020). Links have been made to the Escazú Agreement as a best practice example on requirements for reasoned decision, responding to comments and relying on evidence and to include the option for “a notice of particular interest” to the Scientific and Technical Body, which would allow stakeholders to make their concerns with a planned activity heard (IUCN, Intersessional Work on EIAs, own observation, 2020). Internationalization of the EIA process is a heated debate in the BBNJ negotiations and will ultimately determine the effectiveness of EIAs and the health of the ocean and its ecosystems in the future.

Formal discussions in the BBNJ negotiations have so far not focused on the possibility of a liability fund, which would be important to include into the agreement (Hassanali, 2021). Such a fund would particularly be relevant to cover compensation costs, in the case of court trials requiring time to be resolved and identify responsible actors for pollution/accidents (Tessnow- von Wysocki, 2021).

Setting Priorities for the Planet

While some stakeholders might want to see more focus on conservation (preserving the marine environment), others prioritize sustainable use (the sustainable exploitation of the marine environment for human benefit). How can a balance be achieved in the agreement when the ocean is already largely exploited and little protected (Karan, 2020)? Environmental Impact Assessments are one important aspect of conservation, as they can prevent environmental damage if a strong framework is in place (Tessnow-von Wysocki & Vadrot, 2020). They are also an important pillar for sustainable use of the ocean to allow activities that are not causing harm to the marine environment and still benefit us as humans. Why not use science to evaluate which activities are bearable for the ocean and the organisms that call the ocean their home? And why not re-think activities that turn out to have an adverse effect on the marine environment? The benefits of rejecting harmful activities on the ocean might mean a short-term financial loss – but it also promises a long-term environmental gain. Maybe it would now be the time to see the ocean as part of the planet we live in, rather than an infinite pool of “resources” for us to use? This is the time to set the priorities for the planet and take the first step towards a more sustainable future- with the priority of conserving our planet, rather than exploiting it against the calls of scientists (IPBES, 2019). Future generations will thank us if we take this turn. The protection of the global commons is in everyone’s interest. A fair and effective assessment of human impacts on ocean biodiversity and the decision-making over whether or not to allow activities, require – apart from states – also the inclusion of scientists, non-state actors and interested civil society along the process.

References

Ardron, J. A., Rayfuse, R., Gjerde, K. M., and Warner, R. (2014). The sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity in ABNJ: what can be achieved using existing international agreements? Mar. Policy 985, 98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.02.011

CBD. 2010. What is Impact Assessment? Retrieved from: https://www.cbd.int/impact/whatis.shtml

Crespo, G. O., Dunn, D. C., Gianni, M., Gjerde, K. M., Wright, G., and Halpin, P. N. (2019). High-seas fish biodiversity is slipping through the governance net. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1273–1276. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0981-4

Doelle, M., & Sander, G. (2020). Next Generation Environmental Assessment in the Emerging High Seas Regime? An Evaluation of the State of the Negotiations. The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 35(3), 498-532

Durussel, C., Soto Oyarzún, E., & Urrutia S, O. (2017). Strengthening the Legal and Institutional Frame-work of the Southeast Pacific: Focus on the bbnj Package Elements. The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 32, 671. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718085-12324051

Friedman, A. (2019). Beyond “not undermining”: possibilities for global cooperation to improve environmental protection in areas beyond national jurisdiction. J. Mar. Sci. 76, 452–456. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsy192

Gjerde, K. M., Reeve, L. L. N., Harden-Davies, H., Ardron, J., Dolan, R., Durussel, C., Earle, S., Jimenez, J. A., Kalas, P., Laffoley, D., Oral, N., Page, R., Ribeiro, M. C., Rochette, J., Spadone, A., Thiele, T., Thomas, H. L., Wagner, D., Warner, R., Wilhelm, A., & Wright, G. (2016, 2016/09/01). Protecting Earth’s last conservation frontier: scientific, management and legal priorities for MPAs beyond national boundaries [https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2646]. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 26(S2), 45-60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2646

Hassanali, K. (2021, 2021/03/01/). Internationalization of EIA in a new marine biodiversity agreement under the Law of the Sea Convention: A proposal for a tiered approach to review and decision-making. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 87, 106554. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106554

High Seas Alliance. (2020). Consistency with the Madrid Protocol Thresholds with UNCLOS EIA Provisions. Why the BBNJ Agreement should adopt the Madrid Protocol Threshold and Tiering Approach. Retrieved from: http://www.highseasalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/FInal-Brief-Consistency-of-Madrid-Protocol-Thresholds-with-UNCLOS-9.9.20.pdf

IPBES (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Retrieved from. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3553579

Karan, L. (2020). A Path to Creating the First Generation of High Seas Protected Areas: Science-based method highlights 10 sites that would help safeguard biodiversity beyond national waters. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/03/a-path-to-creating-the-first-generation-of-high-seas-protected-areas

Kok, M., Brons,J., & Witmer, M. (2011). A global public-goods perspective on the environment and poverty reduction: Implications for Dutch Foreign Policy

Livingstone & Jose, (2021). Connectivity of the High Seas to Coastal Waters Retrieved from: http://www.highseasalliance.org/2021/05/21/connectivity-of-the-high-seas-to-coastal-waters/

Ma, D., Fang, Q., & Guan, S. (2016). Current legal regime for environmental impact assessment in areas beyond national jurisdiction and its future approaches. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 56, 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2015.08.009

Marciniak, K. J. (2017). New implementing agreement under UNCLOS: A threat or an opportunity for fisheries governance? Marine Policy, 84, 326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.06.035

O’Leary, B. C., and Roberts, C. M. (2017). The structuring role of marine life in open ocean habitat: importance to international policy. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:268. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00268

O’Leary, B. C., and Roberts, C. M. (2018). Ecological connectivity across ocean depths: implications for protected area design. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 15:e00431. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00431

Sander, G. (2016). International Legal Obligations for Environmental Impact Assessment and Strategic Environmental Assessment in the Arctic Ocean. The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 31(1), 88-119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/15718085-12341385

Scanlon, Z. (2018). The art of “not undermining”: possibilities within existing architecture to improve environmental protections in areas beyond national jurisdiction. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 75, 405–416. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx209

Tessnow- von Wysocki, I. (2021). Developing countries in the BBNJ – CARICOM interests from a blue economy perspective and a proposed approach to EIAs, MARIPOLDATA Ocean Seminar Summary. https://www.maripoldata.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Summary_MARIPOLDATA-Ocean-Seminar_Caricom_slides1.pdf

Tessnow-von Wysocki, I., & Vadrot, A. B. M. (2020). The Voice of Science on Marine Biodiversity Negotiations: A Systematic Literature Review [Systematic Review]. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7(1044). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.614282

Warner, R. (2018, 01/01). Oceans in transition: Incorporating climate-change impacts into environmental impact assessment for marine areas beyond national jurisdiction. Ecology Law Quarterly, 45, 31-51. https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38M61BQ0J

Quirk, G. C., and Harden-Davies, H. (2017). Cooperation, competence and coherence: the role of regional ocean governance in the south west pacific for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Int. J. Mar. Coastal Law 32, 672–708. doi: 10.1163/15718085-13204022

Footnotes:

[1] UNCLOS legal text: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[2] Revised draft text of an agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction, See: https://undocs.org/en/a/conf.232/2020/3

[3] The threshold of impact that triggers an EIA, established in the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol).