‘We are the Ocean’ (Miguel de Serpa Soares, UNDOALOS) – Will highly ambitious statements from the UN Ocean Conference 2022 translate into a highly ambitious BBNJ treaty?

UN Ocean Conference 2022 Blog – IDDRI & MARIPOLDATA

By: Paul Dunshirn, Arne Langlet, Klaudija Cremers

Miguel de Serpa Soares delivering the final remarks of the UN Oceans Conference 2022. Source: own image.

Miguel de Serpa Soares delivering the final remarks of the UN Oceans Conference 2022. Source: own image.

From June 27th to July 1st, the governments of Portugal and Kenya hosted the second UN Oceans Conference (UNOC 2022) in Lisbon.

The conference’s objective was to gather momentum and resources to implement Sustainable Development Goal 14 – ‘Life under Water’ (SDG 14). Its self-proclaimed focus was the role of science and innovation in understanding and counteracting the main threats to ocean ecosystems, and in making ocean-based economic activities sustainable. After a week packed with high-level presentations, panels, and dialogues, delegates unanimously adopted the Lisbon Declaration under the motto ‘Our ocean, our future, our responsibility’.

An estimated 6000 people attended the conference, including 24 heads of state and over 2000 stakeholders from civil society. After a two-year hiatus due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the entire global ocean community welcomed the opportunity to come together and discuss current issues related to sustainable ocean governance. Some of the most debated topics included: a proposed moratorium on deep seabed mining which received support by a coalition of States led by Fiji and Samoa (and gained additional momentum through Emmanuel Macron’s call for a corresponding legal framework); the need for increased financing for ocean sustainability (UN Secretary-General António Guterres highlighted that SDG 14 remains the least funded SDG); opportunities and challenges to build blue economies and blue carbon ecosystems for climate change mitigation; and commitments to embark on negotiations for a legally binding treaty to reduce plastic pollution. Also part of the agenda were the on-going negotiations on an international legally binding instrument on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ negotiations).

Because UNOC 2022 took place only a few weeks before the next negotiation session of the BBNJ negotiations in New York from 15-26 August, it was an important opportunity for stakeholders to discuss the key remaining issues that still need to be addressed in the sidelines of the Conference. The BBNJ instrument – or often times called ‘High Seas Treaty’ – is the central instrument through which UN member States aim to address the declining health of the high seas and its biodiversity, as well as the lack of a comprehensive legal framework for these areas (which constitute no less than ~94% of the world’s ocean volume). The future treaty will have a significant impact on most of the topics that were discussed during UNOC 2022.

French think tank IDDRI and ERC research project MARIPOLDATA attended UNOC 2022 with a special eye for the BBNJ-related events and activities. This blogpost summarises our impressions and discusses implications for the BBNJ IGC-5 in August 2022, keeping a critical view on the concrete proposals and commitments made in Lisbon.

It was particularly noteworthy that member States of the so-called ‘High Ambition Coalition’ were very vocal in promoting and showcasing their position during UNOC 2022. This coalition of States aims for a highly ambitious BBNJ treaty to be concluded in August 2022. In considering the substantive issues at stake, we argue that high ambition statements need to translate into effective legal provisions for the future treaty. This means:

- A clear and easy-to-use legal framework for marine genetic resources, which is crucial to further developing ‘blue economies’.

- BBNJ bodies with firm decision-making powers on environmental impact assessments and on area-based management tools, such as marine protected areas.

- Reliable language in the treaty text to ensure capacity building and technology transfer for developing countries according to the commitments made during UNOC 2022.

‘We want blue economy!’ But what about marine genetic resources?

‘Blue economy’ as a theme was high on the agenda during UNOC 2022. This was expressed during several events and was interpreted to include a wide range of ocean-related economic activities with sustainability focus, including fishing, aquaculture, tourism, up-cycling of waste, or biotechnological applications. While some events focused on the promises of blue innovation, a lot of emphasis was laid on the question of how to achieve more equitable opportunities for countries to participate and profit from these activities (see this report for a discussion on ocean inequities and their significance to blue economy initiatives).

To us as BBNJ researchers, it was notable that many biotechnological applications based on marine genetic resources were presented to promote the blue economy concept, yet with very little consideration of implicated governance issues. While UNOC 2022 was not the place to overcome the persistent divides on accessibility to and benefits derived from marine genetic resources as seen during the BBNJ negotiations, it is important to note that the continued development of many such economic activities requires clear and functional legal frameworks, not least in international waters. This is, however, far from reality at present. In considering the current lack of such a framework for marine genetic resources during a side event on BBNJ, the German Minister for the Environment Steffi Lemke described the situation as ‘similar to the wild west’, pointing to the urgency of the High Ambition Coalition to finalise the BBNJ treaty by August 2022.

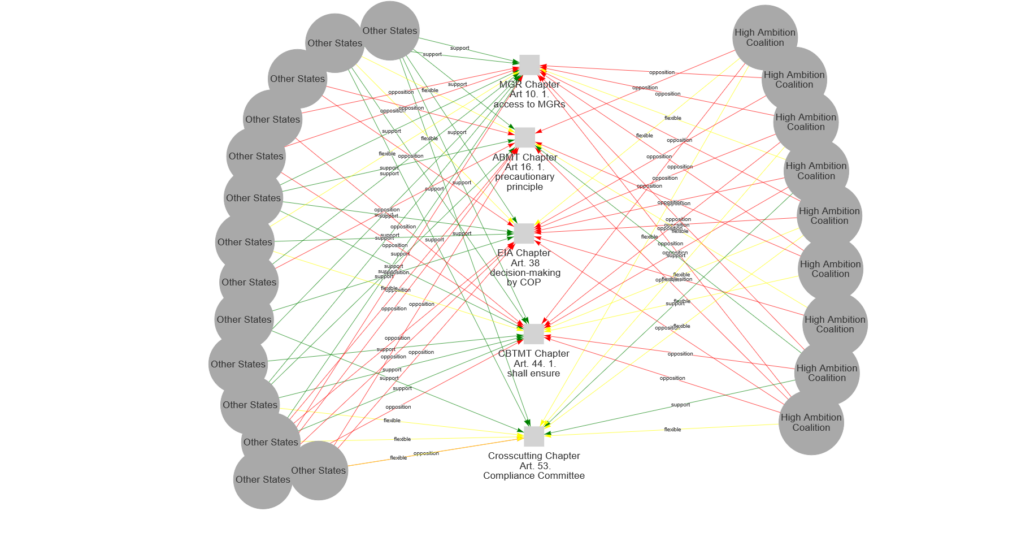

The momentum that emerged during UNOC 2022 is indeed needed to overcome the remaining issues in the BBNJ negotiations – marine genetic resources being the most challenging element left on the table. MARIPOLDATA made a graph that visualises positions of various States on the treaty elements as based on their statements during IGC-4 (see graph ‘BBNJ IGC-4 positions’). As the graph shows, members of the High Ambition Coalition want to limit regulation to the ‘collection’ of genetic materials while leaving later uses of genetic sequence data (‘access’ to genetic resources) untouched. This essentially means that commercial activities that follow up on basic research and intellectual property rights will remain outside the treaty. Other countries and groups (particularly developing countries) emphasised the need to cover both collection and access, as well as to share both monetary and non-monetary benefits derived from marine genetic resources.

Graph: ‘BBNJ IGC-4 positions’ (Colours according to whether states showed support (green), opposition (red) or flexibility (yellow); see interactive version; see Appendix for the underlying methodology).

What we heard from different sources in the sidelines of UNOC 2022 is that there is currently a lack of concrete ideas to help States overcome their differences in their positions on marine genetic resources in the BBNJ context. In this regard, the recent proposal made by the DSI Scientific Network in the Nagoya Protocol context, which includes a decoupling of access and benefit-sharing, combined with a ‘flat-rate’ biodiversity use fee resulting from the commercialization of genetic resources (see also this interview), is relevant. Instead of introducing bureaucratic burdens on scientists or closing open-access databases, this approach constitutes an alternative solution designed to overcome persistent divides, also for the BBNJ context. Finding a practical solution for marine genetic resources that is applicable in both the BBNJ and the Convention of Biological Diversity context would have additional advantages in terms of reducing institutional complexity.

Looking forward to IGC-5, we are confident that States can draw on these and other expert voices to find a solution that promotes the equitable and sustainable use of genetic resources while also setting a clear regulatory framework for the continued conduct of research in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Anchoring the ambitious commitments on capacity building and transfer of marine technology in the BBNJ treaty

Participants at UNOC 2022 often viewed the implementation of SDG 14 as critically dependent on the involvement of the entire global community of States, and emphasised that this has to be based on a fair distribution of marine research and benefits from blue economies. Hence, the importance of sharing knowledge, training, data and technologies was not addressed during a number of side events, but also in an interactive dialogue on June 28th. UNOC 2022 participants also witnessed the launch of a declaration by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) on the enhancement of marine scientific knowledge, research capacity and transfer of technology (CBTMT in BBNJ terms). During this session, marine biologist Dr. Diva Amon made the important remark that the human capacity to research and understand marine ecosystems already exists in many parts of the world, but that the technological equipment to benefit from these capacities is often still lacking. While human-centred training programmes remain important, the transfer of up-to-date marine technologies may become more central in the future. Existing training programmes also need to be improved in light of various forms of discrimation that scientists from developing countries currently have to face in this process.

Many States used the stage UNOC 2022 to emphasise the crucial role of CBTMT for the sustainable use of the ocean and made voluntary commitments in this regard. However, when looking at the graph ‘BBNJ IGC-4 positions’, we see that many States of the High Ambition Coalition were unwilling to accept language that creates legal obligations (‘shall ensure’) in the CBTMT Chapter, and instead preferred to remain vague. We hope that the ambitious commitments on CBTMT voiced during the conference can translate into negotiation positions for BBNJ IGC-5, taking the needs of developing countries seriously and addressing them as concretely as possible.

Deep seabed mining moratorium and the return of the precautionary principle

Deep seabed mining was arguably the most controversial topic during UNOC 2022. As the International Seabed Authority currently prepares for the potential adoption of a mining code during its next council and assembly meetings at the end of July/beginning of August, the governments of Palau, Samoa, Fiji, Guam and 57 parliamentarians from around the world used the stage of UNOC 2022 to announce a global call for a moratorium on deep seabed mining. This call follows a long-standing demand from various States, researchers and civil society organisations to halt deep seabed mining until its environmental impact is better understood. Interestingly, French president Emmanuel Macron also called for a legal framework to ban deep seabed mining during his visit at the conference, adding momentum to the initiative.

At the core of the argument against deep seabed mining is the so-called precautionary principle (see also IUCN’s call for a moratorium), which entails that decision-makers avoid authorising human activities as long as there is not sufficient knowledge about the potential environmental impact of these activities (see IISD definition). This principle has hovered around international environmental treaty-making since the 1992 Rio declaration. During the BBNJ negotiations, it has caused continuous disagreement between those States that want to see it included in the process of identifying marine protected areas, and others that favour the weaker ‘precautionary approach’ (or the ‘application of precaution’, as formulated in the draft from May 2022; see also the MARIPOLDATA Blog on this issue).

The publicly voiced support for the moratorium from the highest political levels thus indicates some momentum for a return to the precautionary principle. During the BBNJ negotiations, we see that many States, that are part of the High Ambition Coalition and have adopted critical stances against deep seabed mining, actually oppose the inclusion of this principle in the area-based management tools chapter (ABMT chapter; see graph ‘BBNJ IGC-4 positions’). If highly ambitious States consider this principle important enough to use it to prevent potentially damaging activities in the seabed, it may be worth also including it in the governance of biodiversity in the water column. While the support of many States and other stakeholders for the 30×30 target on defining (marine) protected areas is an important and welcome step, the adopted legal principles behind these areas also need to be sufficiently ambitious in order to accomplish a treaty that warrants the label of being ‘highly ambitious’.

Ensuring a strong mandate for BBNJ decision-making bodies

The High Ambition Coalition, aims to ‘secure a strong international legal framework, based on science, setting additional legal obligations and environmental tools for effective action’ (Declaration High Ambition Coalition). Its declaration addresses the question of how strong the future institutions of the BBNJ agreement should be. The answer of the ‘highly ambitious’ is: strong. Similarly, the final declaration of UNOC 2022 recognizes the importance of ‘strong governance’ tools for achieving ocean sustainability. As several State representatives from the High Ambition Coalition indicated in Lisbon, the BBNJ conference of parties (COP) should have the mandate to define and implement marine protected areas. At the same time, open questions about decision-making powers remain for other treaty elements. For example, the mandate of the BBNJ COP can still be strengthened in relation to environmental impact assessments.

As MARIPOLDATA’s research from IGC-4 shows (see graph ‘BBNJ IGC-4 positions’), States of the High Ambition Coalition opposed or neglected a cross-regional proposal from CARICOM & PSIDS that aimed to find a compromise while giving the BBNJ COP important competences to critically review activities that endanger the environment. If the High Ambition Coalition wants to change the status quo of unsustainable ocean governance, as German Minister for the Environment Steffi Lemke stated in Lisbon, the coalition members should give the BBNJ COP the mandate and sufficient competencies to review, and, if necessary, prevent harmful activities.

Establishing an effective implementation and compliance committee

In order for the BBNJ treaty to change the status quo of (the lack of) regulation for high seas marine biodiversity and serve as a solid framework to conserve and sustainably use marine biodiversity, it will need to be implemented effectively and States will have to comply with its regulations. Ensuring compliance with international agreements on the high seas is challenging. Therefore, sessions at UNOC 2022 addressed the need to foster institutional partnerships, for example to better control illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Effective implementation and compliance of the law of the sea was also an important issue at BBNJ IGC-4, where a cross-regional proposal by CLAM and PSIDS to establish an implementation and compliance committee was welcomed by many delegations. In this case, the graph on BBNJ positions shows how most countries, and specifically those from the High Ambition Coalition supported this proposal. This should encourage negotiators to continue drafting an effective implementation and compliance committee for the BBNJ instrument.

Moving towards BBNJ IGC-5

Even though the BBNJ agreement is often portrayed as the main instrument to ‘better balance the conservation and sustainable use of marine resources’, advancing discussions on it was not at the centre stage at UNOC 2022. Nonetheless, the events and informal exchanges held in Lisbon have the potential to contribute significantly to the successful conclusion of a strong BBNJ instrument.

Both members and non-members of the High Ambition Coalition still have substantial ground to cover to achieve a truly ambitious BBNJ treaty. High ambition cannot be limited to the fast conclusion of the negotiations, but should be reflected in the substance of the agreement. In the case of marine genetic resources, we pointed to a recent proposal by the DSI Scientific Network for a flat-rate approach to benefit sharing that could help overcome the existing divides in the negotiation. Finding a workable solution that establishes legal clarity and contributes to more equitable participation will be crucial for current and future genetic resource users to engage in ocean-related science. The BBNJ treaty has many implications for the ‘blue economy’ in this regard.

In regards to area-based management tools, the bodies of the BBNJ instrument should not only have a mandate to establish marine protected areas but also to develop and oversee implementation and management plans. Only if given such competences, the BBNJ instrument can make a real difference in protecting sensitive ocean areas. It is similarly important to give the COP of the BBNJ instrument powers to critically deliberate on environmental impact assessments. Finally, if all future parties to the treaty concur that CBTMT is a key element of ocean governance, anchoring concrete CBTMT obligations in the treaty text can help to cement financial predictability and thus gather support among developing countries. Having said that, we are confidently looking towards IGC-5 and the conclusion of this highly important treaty for sustainable and equitable ocean governance.

Systematic data collection by MARIPOLDATA researchers during UNOC 2022. Source: own image.

Appendix: Graph on BBNJ positions

The graph shows the detailed positions of States and alliances on individual provisions of the BBNJ treaty draft text during IGC-4. Due to the prevailing Chatham House rules, we cannot name the individual States but categorise States and alliances either as members of the High Ambition Coalition or as ‘other’. The data was collected by the MARIPOLDATA project during IGC-4, where we traced whether States voiced their support (green), opposition (red) or showed flexibility (yellow) towards some of the key provisions of the BBNJ agreement. The displayed provisions correspond to articles in the revised draft text of November 2019. As we discuss in this blog post, we consider these provisions as crucial to an assessment on how ambitious the BBNJ treaty will actually turn out to be.