Not the only Treaty in the Sea: Linking the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the future BBNJ agreement

This contribution is part of a MARIPOLDATA blog series on current developments and discussions about the negotiations towards an international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). In this series, the team publishes updates on the four package items under the BBNJ Agreement: Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), Area Based Management Tools (ABMTs) including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and Capacity Building and Technology Transfer (CB&TT). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the planned-to-be final intergovernmental conference (IGC) was again postponed and is now planned for 2022. In the meantime, informal exchanges among state and non-state actors are taking place [1]. The MARIPOLDATA blog series include developments from the online Intersessional Work organized by the UN Secretariat since September 2020, the virtual High Seas Treaty Dialogues, taking place under Chatham House rules, organized by 3 states and a number of NGOs, and the MARIPOLDATA Ocean Seminar Series in which scholars and practitioners present and discuss current issues of ocean governance. For this blog, we would like to thank Daniel Kachelriess for his valuable feedback and input.

This contribution is part of a MARIPOLDATA blog series on current developments and discussions about the negotiations towards an international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). In this series, the team publishes updates on the four package items under the BBNJ Agreement: Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), Area Based Management Tools (ABMTs) including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and Capacity Building and Technology Transfer (CB&TT). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the planned-to-be final intergovernmental conference (IGC) was again postponed and is now planned for 2022. In the meantime, informal exchanges among state and non-state actors are taking place [1]. The MARIPOLDATA blog series include developments from the online Intersessional Work organized by the UN Secretariat since September 2020, the virtual High Seas Treaty Dialogues, taking place under Chatham House rules, organized by 3 states and a number of NGOs, and the MARIPOLDATA Ocean Seminar Series in which scholars and practitioners present and discuss current issues of ocean governance. For this blog, we would like to thank Daniel Kachelriess for his valuable feedback and input.

[1] See more information: Intersessional Work organized by UNDOALOS: https://www.un.org/bbnj/content/Intersessional-work and BBNJ Informal Intersessional Dialogues: https://highseasdialogues.org/.

Key arguments

- CITES has a mandate to regulate certain activities with regard to marine species listed under the Convention

- The activities regulated by CITES include activities in ABNJ, leading to the possibility that CITES and the BBNJ treaties may overlap

- A positive formulation of the “not undermining” clause could enhance cooperation

- Implementation of CITES and the BBNJ agreement both requires intensive capacity building efforts (e.g. in ports)

A New Agreement on Marine Biodiversity

The establishment of coherent legal framework for the management and conservation of biodiversity in the High Seas is one objective of the currently ongoing negotiations for a new treaty on marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Treaty) under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (Kulovesi, Mehling, & Morgera, 2019)(Kulovesi, Mehling, & Morgera, 2019). The current draft text for the instrument includes provisions on Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), Area-Based Management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and Capacity Building and Marine Technology Transfer (CBTT), as well as Cross-cutting issues. At the same time, delegates as well as observers constantly highlight that the BBNJ Treaty will have close linkages to other treaties that sectionally or regionally regulate matters related to marine biodiversity. One of these treaties is arguably the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which entered into force in 1975.

CITES

CITES regulates the international trade of endangered species listed on one of its appendices. Appendix 1 includes the most endangered species – threatened with extinction; Appendix 2 includes species that may be threatened with extinction if trade is not closely controlled; and Appendix 3 includes species in need of international trade controls. The Conference of the Parties (COP) to CITES, which takes place every three years, decides upon enlisting new species on their appendices.

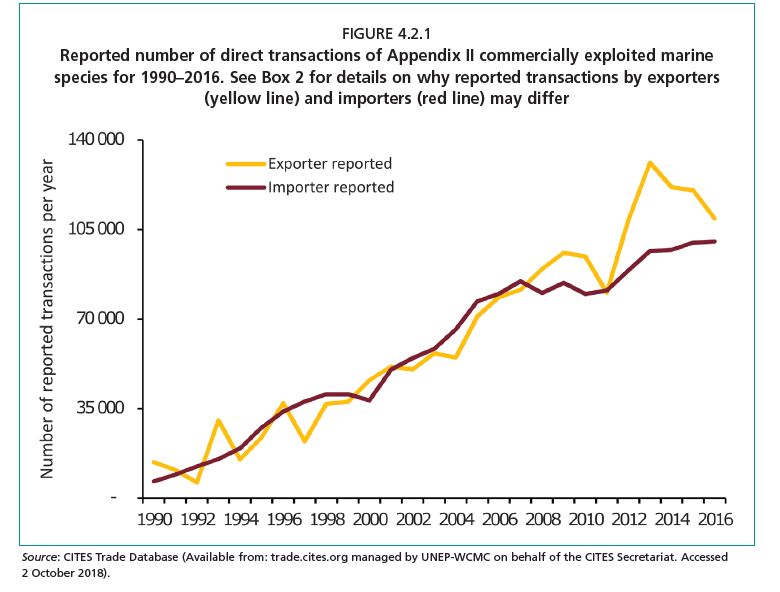

Although CITES initially was largely concerned with terrestrial species, by now, out “of the approximately 39 thousand species currently listed in the CITES Appendices, 2 392 were considered to be marine species” (Pavitt et al., p. 11). With the increasing listing of marine species under CITES, the reported number of trade transactions of marine species has constantly increased as well (Figure 1).

Figure 1: From (Pavitt et al, p.15).

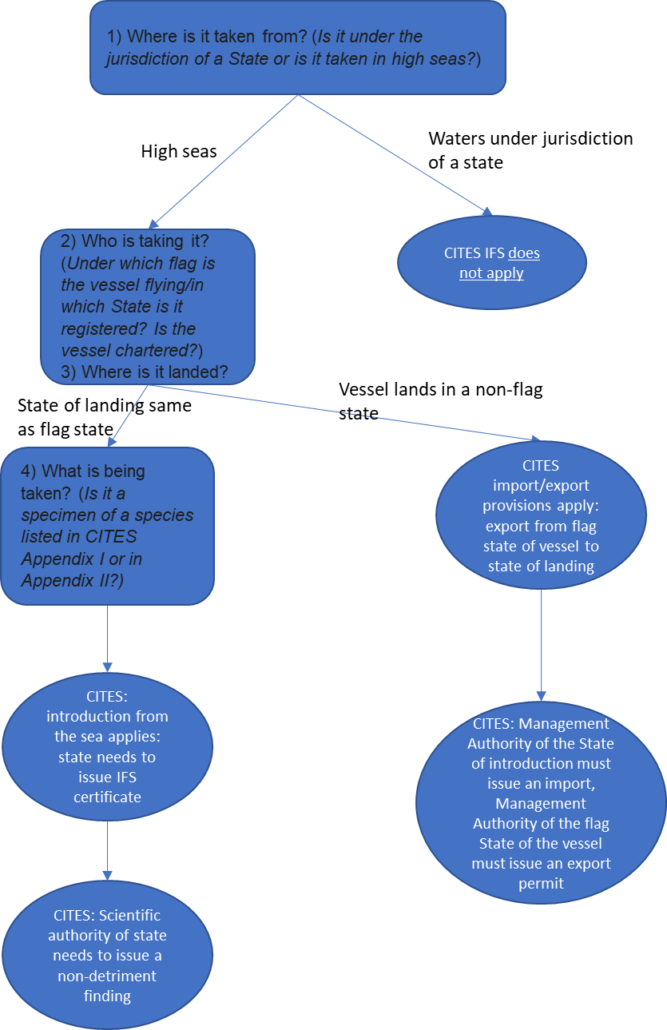

The increasing role CITES plays in relation to marine species is shown in a report recently published by the FAO which presents numbers and trends on trade of commercially exploited CITES-listed marine species. CITES documents and regulates all international trade of listed marine species. By CITES’ definition this includes Introduction from Sea (IFS). “ (the others are import, export, and re-export). IFS is defined in Article 1 of the Convention as transportation into a State of specimens of any species which were taken in the marine environment not under the jurisdiction of any State.” This addresses areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) – which is the same geographical scope that the BBNJ treaty aims to cover. Although, this provision was initially not operationalized, partially due to the limited number of marine species listed under CITES, COP 16 in 2013 adopted guidance in Resolution Conf. 14.6 (Rev CoP16) that specified for different scenarios when an IFS certificate or other type of permit that allows the further trade of this species is required.

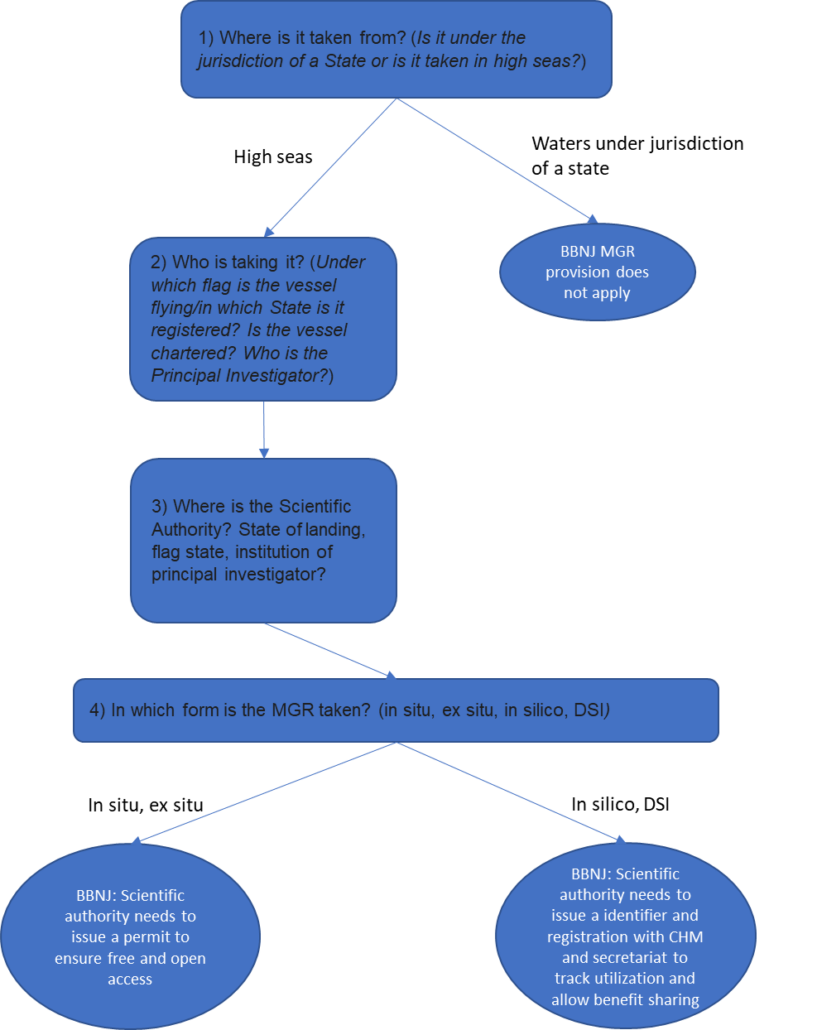

Controlling the flow of MGRs

As observed by Kachelriess, Cremers and Wright in the recent blog post of IDDRI, “the current BBNJ draft agreement shares many characteristics with IFS”, particularly in the MGR part. In fact, CITES could already now regulate the access and trade of MGRs in ABNJ when they stem from a species under Appendix 1 or 2 of CITES. The similarities can be seen in Figure 2. The depicted process for MGR registration and access is largely simplified and summarizes some states’ ideas presented by the CITES secretariat in a flowchart in spring 2021. Indeed, MGRs under BBNJ and the IFS share similarities in that both systems come into action when a specimen is taken from ABNJ. One large unresolved question in the BBNJ system is who would be the responsible authority to register the MGR sample and ensure access and a potential tracking mechanism for benefit sharing. The IFS system can bring some clarity to the BBNJ negotiations because it operationalizes the location of the authority to implement regulations in cases when there is no state authority to “provide” the specimen.

It specifies that the national authority of the vessel at hand carrying the MGRs needs to issue an IFS certificate if the vessels lands in its flag state. When the landing state (where the vessels enter into harbor after the capture) differs from the flag state, the landing state needs to issue an import permit and the flag state under which the vessels operates, needs to issue an export permit. Both scenarios involve a “Scientific Authority” to issue a non-detriment finding if the specimen is listed under appendix 1 or 2 of CITES. A non-detriment finding under CITES is a document, issued by a Scientific Authority that specifies that the transaction is not to the detriment of the specimen based on population status; distribution; population trend; harvest; other biological and ecological factors; and trade information. The issuing of this document requires scientific knowledge on the indicated factors and an Scientific Authority that can document these.

Hence, CITES establishes that parties to the convention need to have a Scientific Authority that is in the position to scientifically assess the condition of the population from which the specimen was landed by a vessel and identification at the port of entry to determine if the specimen at hand is listed under appendix 1 or 2 of CITES. The notion of an authority (e.g. fisheries or port inspectors) with some level of scientific knowledge that assesses what was landed and how to handle it in terms of international regulation may be interesting for BBNJ purposes as well. Although, not specifically termed “Scientific Authority” there has been debate in the ongoing BBNJ negotiations on who would have to report and register the MGRs at hand to the CHM and/or the secretariat of the BBNJ.

Figure 2: Author´s worked, based on https://cites.org/eng/prog/ifs.php and on flowchart handed out by BBNJ secretariat on 16.03.2021

CITES Introduction From Sea clause BBNJ Marine Genetic Resources monitoring draft

How to proceed with two “not undermining” clauses

In order not to undermine existing agreements, the current BBNJ treaty draft pursues to regulate the “Relationship between this Agreement and the Convention and relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies” (Revised Draft of November 27, 2019, art. 4). In this Article, it is specified that “this Agreement shall be interpreted and applied in a manner that [respects the competences of and] does not undermine relevant legal instruments and frameworks” (Revised Draft of November 27, 2019, art. 4, para. 3).

Similarly, CITES makes clear that nothing in the text of its Convention “shall prejudice the codification and development of” UNCLOS (art. 14). As the BBNJ agreement is negotiated as an implementing agreement of UNCLOS, CITES provisions may not infringe or overrule the BBNJ treaty. Depending on how these two mirroring provisions are interpreted, it may mean that CITES may not be applicable if relevant law exists under UNCLOS. This may come as a surprise as negotiators in BBNJ aim to carefully avoid to undermine any other legal instrument. Depending on the exact formulation of these provisions, there is the danger that both agreements leave species from ABNJ less protected than they currently are out of a fear to undermine an existing agreement. In fact, having a clause not to undermine other agreements is common in international treaty making. Nevertheless, this should not be a reason for negotiators to cut down on ambition in the new treaty. On the opposite, it has been shown how international agreements can also act in a cross-supportive way through cooperation or deference when their competences touch and, in this way, strengthen compliance (Downie, 2021; Pratt, 2018).

CITES was negotiated prior to the current international framework for fisheries management in ABNJ, the 1995 fish stocks agreement and most of the RFMOs, being established. This had changed by 2013, when the IFS provision was operationalized and these treaties and bodies already existed. However, RFMOs and their state parties did not oppose the operationalization of the IFS clause out of fear to undermine RFMOs. In fact, the initiative to make the IFS clause operable came from a Fábio Hazin who had ample experience in fishery bodies (ICCAT). Instead of fearing mutual undermining, representatives realized the potential of synergies between RFMOs and CITES. The UN Fish Stocks Agreement foresees in Article 8.6 that competences may be shared, actively allowing for interinstitutional cooperation (Caddell, 2019). This means that CITES was able to complement the existing institutional framework and to play a supportive role for the protection of fish.

Having this in mind, the relative minor role that CITES has played in the ongoing BBNJ negotiations seems surprising. Few states have referred to the importance of CITES in relation to the BBNJ (Algeria, Mauritius and Israel) but the experience from CITES could teach delegates negotiating the BBNJ agreement not to refrain from strong protective provisions in the fear to undermine another international treaty. This was highlighted by different non-governmental actors during the long intersessional period of the BBNJ negotiations. During this period, non-state actors emphasized how CITES and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations complement each others’ mandates and successfully share competences for conservation of fish stocks in different regions. In light of these insights, we highlight that a mutual ‘not undermining’ should not be formulated negatively but rather in a positive, proactive manner, strengthening the protective measures put in place under CITES.

BBNJ and CITES share a focus on capacity building

Instead of concentrating on ‘not undermining’ it could be worthwhile to look at common areas that could be strengthened by both instruments cooperatively. Similarly to CITES, the BBNJ agreement will have to be implemented through national legislation and national authorities (Kachelriess, Cremers and Wright, year). This means, that the implementation of some of the BBNJ provisions (on MGRs for example) could build on the same state authorities and scientific authorities that already have a role under CITES. When the discussions on CBTT in the BBNJ negotiations move towards who will be the beneficiary of capacity building measures, it seems worthy to understand concretely what kind of institutions and authorities are needed to implement the foreseen measures. Negotiators do not have to re-invent the wheel but a look at CITES can give insights into what national (scientific) authorities are required. The experience with CITES can also teach BBNJ implementation about potential challenges in capacity building needs. It would be mutually beneficial if BBNJ acknowledges the role of these authorities and strengthens them through increased capacity building instead of identifying new actors and institutions on the national level that are expected to enforce treaty provisions.

As shown in the previous workflow on MGRs and IFS, national authorities that are present in the ports and scientific authorities that control the origin and type of species are needed to implement both CITES and BBNJ. Capacity building in the BBNJ agreement could thus simultaneously strengthen the same national capacities to monitor and assess high seas biodiversity that have been supported by CITES. Understanding the implementation of CITES, BBNJ could similarly pursue a collaborative, non-adversarial implementation approach through national laws and support for national authorities.

Conclusion

The Introduction from Sea (IFS) clause lay dormant in CITES’ mandate from 1973 until Parties agreed on guidance how to implement it in 2013. The increased attention by CITES Parties to list marine species under CITES was in response to a significant and dangerous gap in regulation of endangered marine species. Since then the number of CITES regulated marine species and the amount of registered transaction has constantly increased. Because the future BBNJ agreement also aims to conserve marine species, both treaties may end up overlapping in their mandate. In order to prevent conflicts of competences and legal inaccuracies, the BBNJ agreement possesses an “not undermining” clause which specifies that the Treaty shall not undermine other relevant instruments. However, also CITES (and many other agreement) possesses such a clause. This may lead to mutual inaction out of fear to “undermine” each other. Therefore, this blog suggests that the “not undermining” clause could be reformulated into positive language that enhances cooperation between the agreements to support mutual implementation. For a successful implementation of the BBNJ agreement, a look at CITES could help. For example, the IFS work-flow to check whether an organism falls under the IFS clause shows similarities to a potential MGR work-flow controlling the applicability of the MGR provisions. Further, the key actors to monitor IFS (and potentially MGR) provisions will be authorities in ports where vessels from ABNJ land. These require robust scientific knowledge in order to effectively monitor these provisions. The chances for capacity building to support implementation of both – CITES and BBNJ – should be highlighted and used.

References

Caddell, R. (2019). International Fisheries Law and Interactions with Global Regimes and Processes. In R. Caddell & E. J. Molenaar (Eds.), Strengthening International Fisheries Law in an Era of Changing Oceans (pp. 133-163): Hart.

Downie, C. (2021). Competition, cooperation, and adaptation: The organizational ecology of international organizations in global energy governance. Review of International Studies, 1-21. doi:10.1017/S0260210521000267

Kulovesi, K., Mehling, M., & Morgera, E. (2019). Global Environmental Law: Context and Theory, Challenge and Promise. Transnational Environmental Law, 8(3), 405-435. doi:10.1017/S2047102519000347

Pratt, T. (2018). Deference and Hierarchy in International Regime Complexes. International organization, 72(3), 561-590. doi:10.1017/S0020818318000164

CITES (n.d.). Introduction from the Sea. Retrieved from https://cites.org/eng/prog/ifs.php